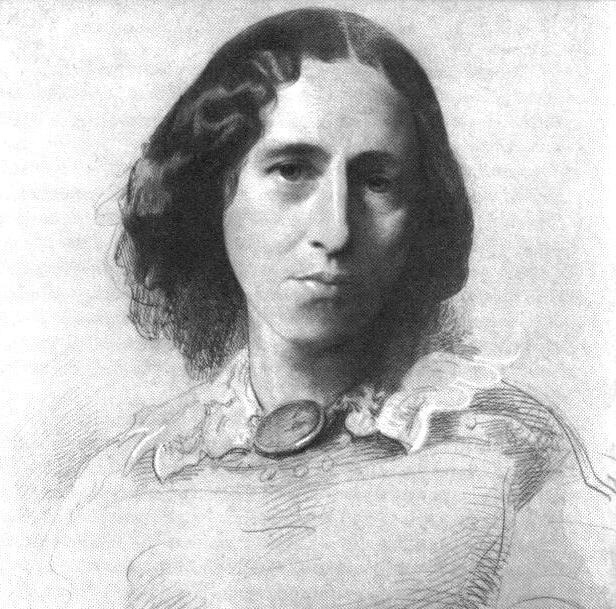

Philosopher Richard Norman on the broad and generous humanism of novelist George Eliot.

George Eliot was a great humanist, and a great English novelist – perhaps the greatest. Born in 1819 in Warwickshire, she was in her teens a fervent evangelical Christian but then reacted strongly against it. She moved to Coventry in 1841 and increasingly mixed in radical and free-thinking circles. A voracious reader and self-educator, she was persuaded to translate into English two major works of German sceptical thought, David Friedrich Strauss’s The Life of Jesus, which sought to separate the historical Jesus from the supernatural accretions of miracles and myth, and Ludwig Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity, which presented religious belief as a human creation and a projection of human qualities. Her translation of these two books places her at the heart of the nineteenth-century rejection of traditional Christianity.

Several years later, in a letter to friends in 1859, the year of the publication of her first novel Adam Bede, she wrote:

I think I hardly ever spoke to you of the strong hold Evangelical Christianity had on me from the age of fifteen to two and twenty and of the abundant intercourse I had had with earnest people of various religious sects. When I was at Geneva, I had not yet lost the attitude of antagonism which belongs to the renunciation of any belief – also, I was very unhappy, and in a state of discord and rebellion towards my own lot. Ten years of experience have wrought great changes in that inward self: I have no longer any antagonism towards any faith in which human sorrow and human longing for purity have expressed themselves; on the contrary, I have a sympathy with it that predominates over all argumentative tendencies. I have not returned to dogmatic Christianity – to the acceptance of any set of dogmas as a creed, and a superhuman revelation of the Unseen – but I see in it the highest expression of the religious sentiment that has yet found its place in the history of mankind, and I have the profoundest interest in the inward life of sincere Christians in all ages… although my most rooted conviction is, that the immediate object and the proper sphere of all our highest emotions are our struggling fellow-men and this earthly existence.

It is that broad and generous humanism that I admire – one which recognises the impossibility of returning to religious creeds and dogmas but is prepared to sift out what is of value in the religious impulse.

The many and differing faces of Christianity are one of the themes of her novels. In her greatest novel, Middlemarch, they are represented by the banker Bulstrode, a hypocritical evangelical whose surface piety hides a shameful secret; the desiccated clergyman-scholar Casaubon, whom Dorothea makes the mistake of marrying; and Mr Farebrother, not really cut out to be a clergyman but with a true and sympathetic heart.

The two central characters of Middlemarch, Dorothea and Lydgate, both start out with high ambitions to do something for their ‘struggling fellow-men’. Their hopes are frustrated. At the end of the novel Lydgate, despite being a successful doctor, ‘regarded himself as a failure’ because ‘he had not done what he once meant to do’. Of Dorothea we are told, in the final paragraph: ‘Her finely-touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature… spent itself in channels which had no great name on earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive…’ I love that phrase – ‘incalculably diffusive’. George Eliot recognised that our lives are interwoven, and though we may not know what effect we will have on others, we can trust that by endeavouring to live well we can all make our contribution to ‘our struggling fellow-men and this earthly existence’.

This post is part of a series written by members, friends and Distinguished Supporters of the British Humanist Association about their own “humanist heroes”.

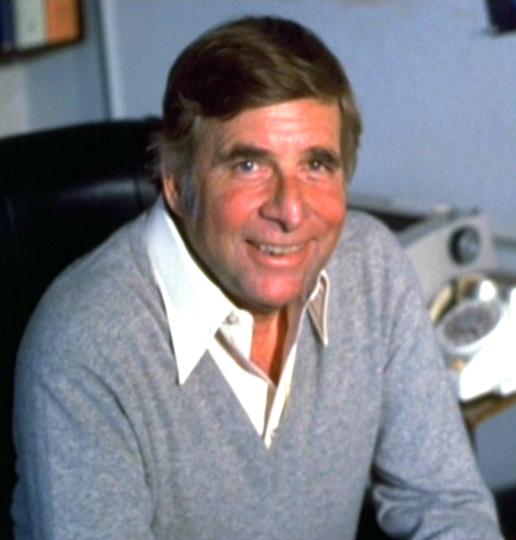

Richard Norman is Emeritus Professor of Moral Philosophy, founder-member of the Humanist Philosophers’ Group, and a Vice-President of the BHA. His book On Humanism is available from the BHA Amazon store.