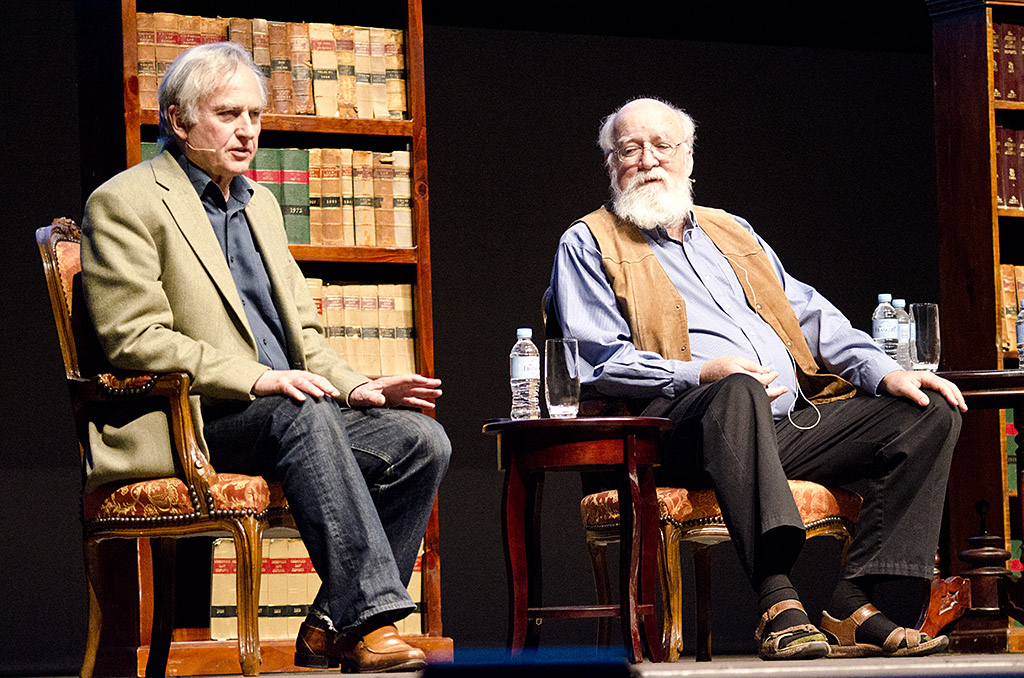

Are the ‘new atheists’ undermining the international Humanist movement? Pictured: Richard Dawkins and Daniel Dennett at the 2012 Global Atheist Conference.

Humanists, secularists and rationalists everywhere are becoming increasingly concerned – even alarmed – at the role being played by traditional religions the world over in promoting instability and violence. Not long ago traditional religions seemed like an anachronism that would fade away with the growth of science and rationality. That has not happened. Science, as knowledge of the physical world, has hardly had any effect on the mindsets of millions of ordinary people. On the other hand technology, spawned by science, has had a profound effect on the way every individual on this planet lives. Among other things, technology has put enormous destructive power in the hands of individuals and small groups. Now a small group of fanatics – even an individual – can cause more death and destruction than a whole army could even a hundred years ago. With the tensions created by increasing migrations and interpenetration of cultures, such groups can pop up anywhere. In societies which are at the receiving end of these transitions there is an understandable sense of insecurity. Traditional religion is seen as an evil that has to be combated.

The Amsterdam Declaration of 2002, the official defining statement of World Humanism, states: “Humanism is a response to the widespread demand for an alternative to dogmatic religion.” This is more specific than the Amsterdam Declaration of 1952: “This congress is a response to the wide spread demand for an alternative to the religions which claim to be based on revelation on the one hand, and totalitarian systems on the other.” Religion was not seen as an unmitigated evil, but perhaps as a necessary stage in the evolution of human society which now had to be outgrown. It would not be correct indiscriminately to tar – or gild – all religions with the same brush. As Narsingh Narain said: “…an analysis is necessary for a proper understanding of the complex phenomena which have been grouped under the name ‘religion’, so that we can build our own organisation on solid foundations and also be able to have a sympathetic understanding of the faiths of other groups.” This sympathetic understanding must, of course, extend to all religions – even to the ones that are most antagonistic to humanist values.

Over the last few years it has become increasingly clear that the objective of providing an alternative to traditional religions has lost its salience for the Humanist Movement. Other issues and causes, undoubtedly worthy in themselves, have caused attention to be diverted from the main aim. To the extent to which it does engage with traditional religions, Humanism has mainly adopted an attitude of rejection and ridicule. The “sympathetic understanding” is missing. If the vast masses of people have to be weaned off their dependence on the myths and divisive dogmas of traditional religions, this sympathetic understanding is indispensible. Humanism has to see itself as a successor to traditional religions, not as an enemy.

Freedom of thought is a prime Humanist value: dogmatism is its very opposite. Some religions are more dogmatic, and therefore more intolerant, than others. These religions, in other words, are more ‘hard’ (dogmatic and intolerant) than others. The Humanist Movement, to achieve its objectives, has to identify the religions which offer the greatest resistance to its efforts to advance Humanist values. For this it is necessary to grade religions according to their ‘hardness’.

At the bottom of the scale would be the ‘softest’ religions – perhaps Jainism and Buddhism. Above these, there are several major religions whose numerous denominations could occupy different positions on the scale. The top positions probably go to certain denominations of the three Abrahamic religions. Gore Vidal (who passed away recently) once wrote: “The great unmentionable evil at the centre of our culture is monotheism.” This is in line with Ralph Peters’ comment: “All monotheist religions have been really good haters. We just take turns.” With 2.2 billion and 1.7 billion respectively, Christianity and Islam have the largest number of adherents in the world. Certain denominations of these two religions – Catholics in Christianity and Wahhabis in Islam – can fairly be put on top of the list. The Unitarians and Sufis perhaps have a place on the soft end of the scale.

What, one might ask, is the point of this classification?

First: it helps to remind us of our original commitment to provide an alternative to dogmatic religions.

Secondly: It helps to determine our priorities when dealing with various religions. It helps us to shed the habit of tarring all religions with same brush as typically summed up by Dawkins: “I think there’s something very evil about faith.

Thirdly: having determined our priorities when dealing with various religions, it helps us to strategise better. One way to strategise is to treat this on the principles of geopolitics, treating the major traditional religions as nation-states. In any case, in the real world, religion (especially the Abrahamic religions on which we have to focus) and geopolitics are inextricably mixed up. Evangelical Christianity and radical Islamism (and perhaps Orthodox Judaism, demographically insignificant but politically powerful) are now in almost open confrontation. As a recent article in the New Statesman says: “Puritanical yet wealthy, convinced of their God-given mission to the rest of the world, sure of a divinely inspired history… Saudi Arabia and the United States are surprisingly similar in their mixture of religion, politics and interference in other countries’ affairs. Saudi Arabia has Wahhabi Islam, Middle America has evangelical Christianity. Historically, they hate each other. Yet both see themselves as exponents of the purest version of their faith. Both are suspicious of modernity. Both see no distinction between politics and religion.”

This complicates matters for the Humanist movement considerably. Whereas one of the main protagonists in this situation, Evangelical Christianity, is an easy target for the Humanist movement, the other major – and arguably more formidable protagonist: Radical Islam, is almost totally out of reach. (Except possibly in the United Nations, where significant work, ably led by Roy Brown, has been done). The result is that the Humanist movement, confined to the West, keeps skirmishing with the various Christian denominations – some of them harmless – while it is almost totally absent from the Islamic world. The IHEU has 112 member organisations in 37 countries. Currently the UN has 192 member states. Only four Islamic states, Nigeria, Egypt, Bangladesh and Pakistan have member-organisations of IHEU. What their state of health is can only be guessed. It is perhaps fair to say that the Humanist Movement has mostly been confined to the West. A cynical friend once remarked that the footprint of the IHEU is more or less the same as that of NATO. There is no evidence that there is – or indeed can be – any plan to remedy this situation. However, inexplicably, there are hardly any efforts being made to contain the growing influence of radical Islamic diaspora even within the West.

In recent years, as the depredations of terrorists and fanatics have increased, leading humanists in the West have adopted a more and more hostile attitude towards traditional religions. If the minds and hearts of traditional religionists have to be won, this is bound to be counterproductive. Rejection and ridicule have to be replaced with persuasion. The rise of hardline New Atheism, with its indiscriminate condemnation of all religions, can undermine the efforts of the Humanist movement to achieve its objectives. According to Michael Ruse: “… there is the nigh-hysterical repudiation of religion. As with religions themselves, the implication is that those who fail to follow the New Atheist line are not just wrong, but morally challenged.” This itself borders on dogmatism.

The conclusion seems to be that the International Humanist Movement has not made any significant progress towards achieving its basic goals. Where it is undoubtedly needed most – in the Islamic world – it is practically absent; where it does have a strong presence – in North America and Europe – it has failed to have an impact. Clearly, we need to rethink our aims and strategies. We must not allow ourselves to be distracted from our original aim of providing an alternative to dogmatic religions.

As of now, one is reminded of what Matthew Arnold had to say of the atheistic poet Shelley, describing him as “a beautiful and ineffectual angel, beating in the void his luminous wings in vain.”