by Mike Flood

In May, Milton Keynes Humanists held a meeting on ‘Cultural Diversity,’ at which we explored various ways in which social scientists had attempted to describe and classify different cultures. We were particularly interested in the work of Geert Hofstede, and we thought it would be fun to see how our group scored on the different dimensions of culture that he has identified. For a small fee (€20), the Hofstede Centre will analyse your preferences and predilections and tell you how much (or how little) you diverge from the norm. And you can choose another country and the Centre will give you advice on how to avoid potential intercultural pitfalls if you were to venture there.

In May, Milton Keynes Humanists held a meeting on ‘Cultural Diversity,’ at which we explored various ways in which social scientists had attempted to describe and classify different cultures. We were particularly interested in the work of Geert Hofstede, and we thought it would be fun to see how our group scored on the different dimensions of culture that he has identified. For a small fee (€20), the Hofstede Centre will analyse your preferences and predilections and tell you how much (or how little) you diverge from the norm. And you can choose another country and the Centre will give you advice on how to avoid potential intercultural pitfalls if you were to venture there.

We were curious to see how our collective response — albeit from a small, self-selected group — would compare with the UK as a whole. It also led us to speculate on whether specific cultural traits make some countries more or less likely to embrace Humanism (or organised religion for that matter).

In terms of the proportion of the population that say they are humanists, I understand that Norway is top of the world table, followed by the Netherlands and the UK; in terms of sheer numbers, it is India. However, counting humanists is fraught with danger as there is no consensus on how to define a humanist: should one include only self-professed humanists (as in India, where humanists are closely linked with the pro-democracy and pro-human rights movements), or only paid-up members of humanist groups; or should we also include people who hold broadly humanist views but who do not think of themselves as humanist? And if this last category, how do you count them? Polls suggest that 47% of Chinese think of themselves as ‘convinced atheists’ and 31% of Japanese,[1] but we don’t think of China and Japan as being particularly ‘humanist’ despite the strong influence of Confucious.

What is Culture?

Culture is an intriguing phenomenon and not something anyone can satisfactorily measure. It is specific to a particular racial, religious, professional or social group, or to society at large. It is something that is learned not something we are born with, and in this respect it is unlike human nature (which is universal and inherited) and personality (which is specific to the individual and both inherited and learned). In essence culture is “shared knowledge used by people to inform, influence or govern their behaviour and determine how they see and experience the world”. It is transmitted through social and institutional traditions and accepted norms to succeeding generations; and paradoxically, it is changing constantly whilst many of its characteristics remain the same.[2] One can however compare cultures in respect of defined characteristics, like individualism or assertiveness, or whether people have a tendency to express their feelings in public. And this is the approach that Hofstede pioneered back in the 1960s.

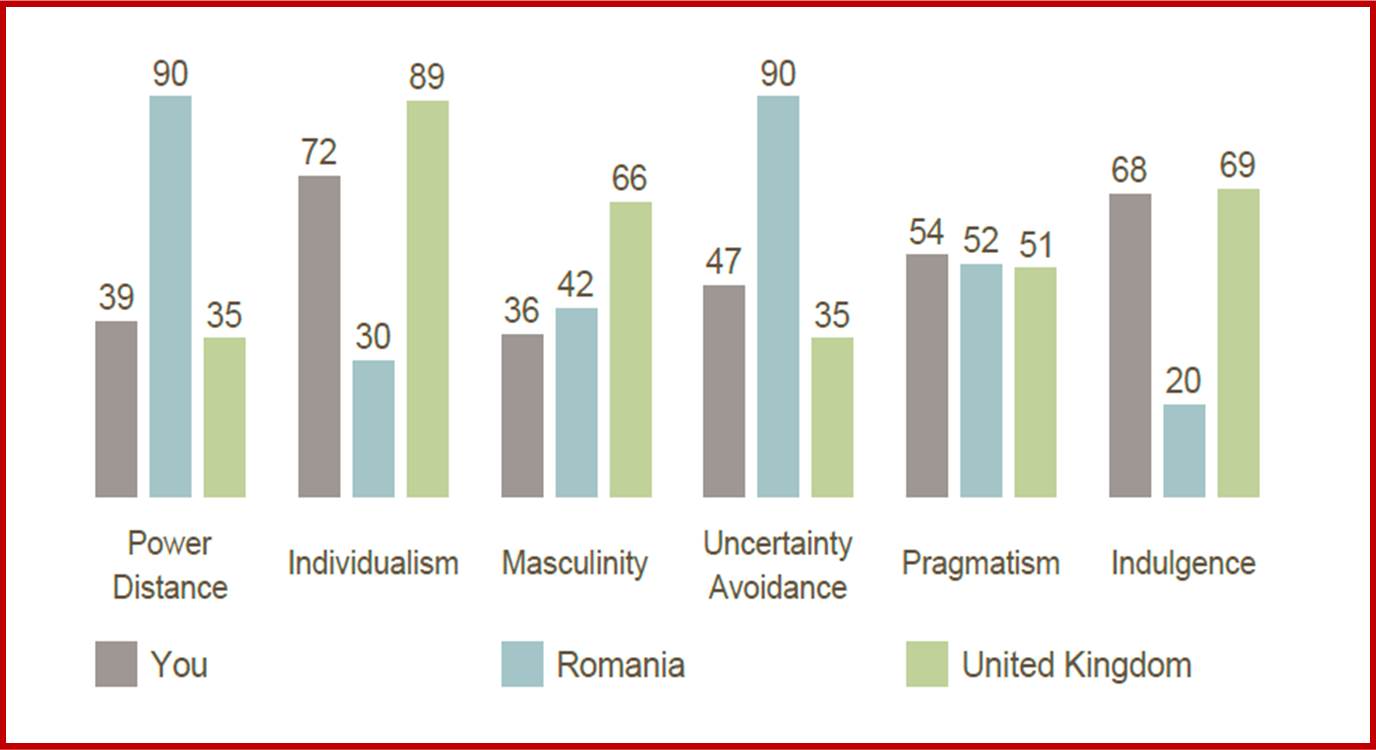

Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture

Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture

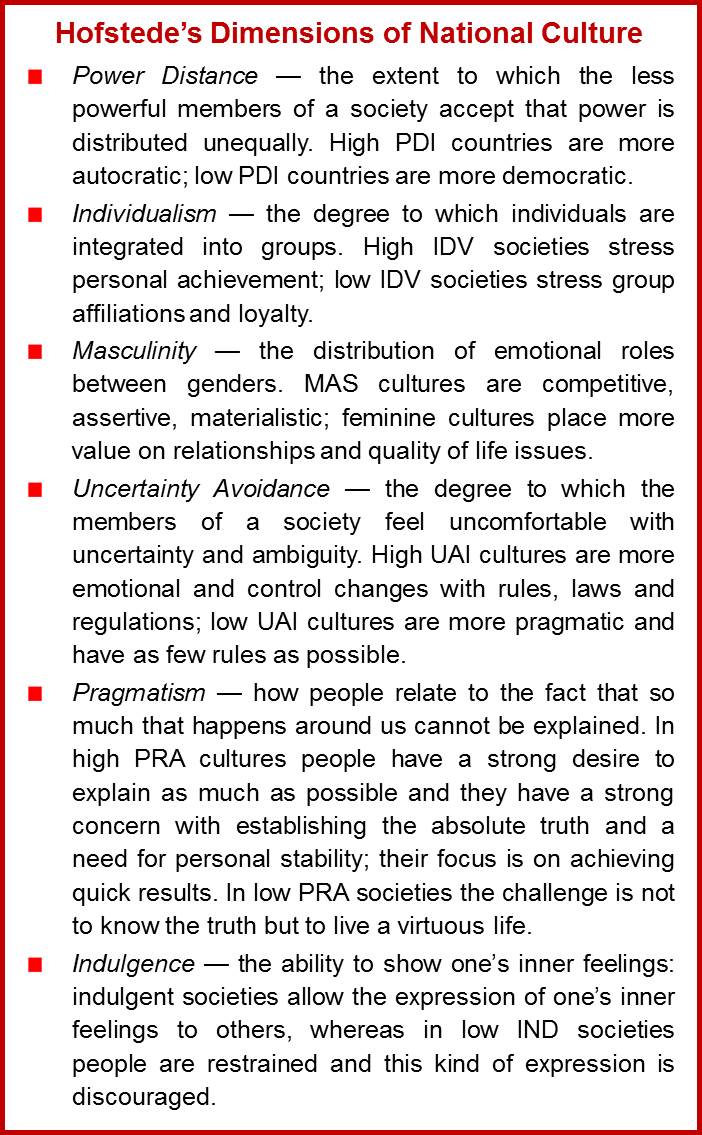

Professor Hofstede started on this line of work when he was asked by IBM to try to find out why company HQ was getting such divergent feedback from staff in its regional offices. The company wanted to better understand how culture was influencing workplace values and performance. Hofstede analysed data from more than 70 countries and proposed that the values that distinguished cultures could be understood in terms of four basic dimensions — ‘Power Distance’ (PDI), ‘Individualism’ (IDV), ‘Masculinity’ (MAS) and ‘Uncertainty Avoidance’ (UAI). These are briefly described in the box below. Some years later Hofstede added two more, ‘Pragmatism’ (PRA) and ‘Indulgence’ (IND), following research by other social scientists.[3]

Hofstede scores each country on a scale of 1 to 100 for each of these six dimensions. He has found, perhaps surprisingly, that the relative scores turn out to be quite stable over time despite the many uncertainties. The forces that cause cultures to shift tend to be global or continent-wide so if countries’ cultures shift, they shift together and their relative positions remain the same. Moreover, individual country scores do seem to correlate with other data, for example, Power Distance with income inequality; Individualism, with national wealth; Masculinity, related negatively with the percentage of national income spent on social security; Uncertainty Avoidance, associated (in developed countries) with the legal obligation for citizens to carry identity cards; and Pragmatism, connected to school mathematics results in international comparisons!

British Culture

If you look at British culture through the lens of the Hofstede 6-D Model you find that we have high scores on INV, MAS and IND — indeed, at 89 the UK is amongst the highest of the individualistic scores. The figure for Masculinity (66) is lower, but Britain is still ‘highly success oriented and driven’; and the figure for INV (69) suggests that we ‘exhibit a willingness to realise our impulses and desires with regard to enjoying life and having fun.’

If you look at British culture through the lens of the Hofstede 6-D Model you find that we have high scores on INV, MAS and IND — indeed, at 89 the UK is amongst the highest of the individualistic scores. The figure for Masculinity (66) is lower, but Britain is still ‘highly success oriented and driven’; and the figure for INV (69) suggests that we ‘exhibit a willingness to realise our impulses and desires with regard to enjoying life and having fun.’

By contrast, Britain sits in the lower rankings of PDI (35); and we also have a low score on UAI (35), which means that as a nation we are ‘quite happy to wake up not knowing what the day brings’ and ‘make things up as we go along’; we are also ‘comfortable in ambiguous situations — the term “muddling through” is a very British way of expressing this’. With the sixth dimension, PRA, the UK has an intermediate score (51), which suggests no dominant preference, neither a strong desire to explain as much as possible (normative), nor people believing that “the challenge is not to know the truth but to live a virtuous life’ (pragmatic).[4] Interestingly, the profile for the UK is remarkably similar to that of Norway and the Netherlands with the one major exception of Masculinity (UK, 66; Norway, 8; Netherlands, 14).

Milton Keynes Humanists

Milton Keynes Humanists is a typical BHA group: we have a mailing list of around 70 and an average turnout at monthly meetings of between 20 and 25; and we are gender-balanced, with significantly more older than younger people. We also have a (younger) virtual community on Facebook which can reach over 150 — 55% of the 110 individuals who have so far ‘liked’ our site and under 45.

We invited 30 of our regulars to fill out the Hofstede Centre’s questionnaire and 15 obliged. The survey measures personal preferences against 42 pairs of statements which one is asked to score on a scale of 1 to 5. It is a little disconcerting to find that the two opinions sometimes refer to rather different issues, for example, ‘Most people can be trusted’ (1) is paired with ‘When people have failed in life it is often their own fault’ (5); and ‘People who live a totally different life than me are interesting’ (1), with ‘Strangers have to earn trust before they will be accepted’ (5). However, the organisers advise you to “listen to your heart rather than your head” when making a selection.

We registered as a ‘long term visitor’ in respect of our ‘other country’ (rather than ‘student’ or ‘negotiator’) and completed the form on line. The Centre then compared our preferences with the UK as a whole (our ‘home country’) and the country we selected, Romania (as explained below). And by return we received a report with a histogram (note ‘You’ = MKH) and a set of specific, cultural pitfall-avoiding recommendations based on the answers we submitted. In our case, ‘you may wonder why people (from Romania) either try to structure their life as much as possible or are fatalistic’ and ‘you may be confronted by people who first behave very kindly and who then suddenly behave as if a curtain has been closed or a glass wall has been erected between them and you’, and many more observations, words of advice…

To prepare our group’s profile we averaged the scores and chose the closest integers; and where the average was X.4, X.5 or X.6 we made an assessment based on the score chosen by the majority. We are not making any great claims for this exercise, only that our results are interesting and deeply thought-provoking. For example, it turns out that our members are close to the UK norm in three of the Hofstede dimensions (PDI, PRA & IND) but 45% lower in Masculinity, 19% lower in Individualism, and 34% higher in Uncertainty Avoidance. Whether the gender make-up of our small sample (60% men; 40% women) significantly influenced the results is not clear. And we should also repeat the Centre’s caveat that one’s scores are ‘only an approximation on Hofstede’s dimensions and not scientifically valid, because culture does not exist at an individual level’.

To prepare our group’s profile we averaged the scores and chose the closest integers; and where the average was X.4, X.5 or X.6 we made an assessment based on the score chosen by the majority. We are not making any great claims for this exercise, only that our results are interesting and deeply thought-provoking. For example, it turns out that our members are close to the UK norm in three of the Hofstede dimensions (PDI, PRA & IND) but 45% lower in Masculinity, 19% lower in Individualism, and 34% higher in Uncertainty Avoidance. Whether the gender make-up of our small sample (60% men; 40% women) significantly influenced the results is not clear. And we should also repeat the Centre’s caveat that one’s scores are ‘only an approximation on Hofstede’s dimensions and not scientifically valid, because culture does not exist at an individual level’.

Humanist Friendly Cultures?

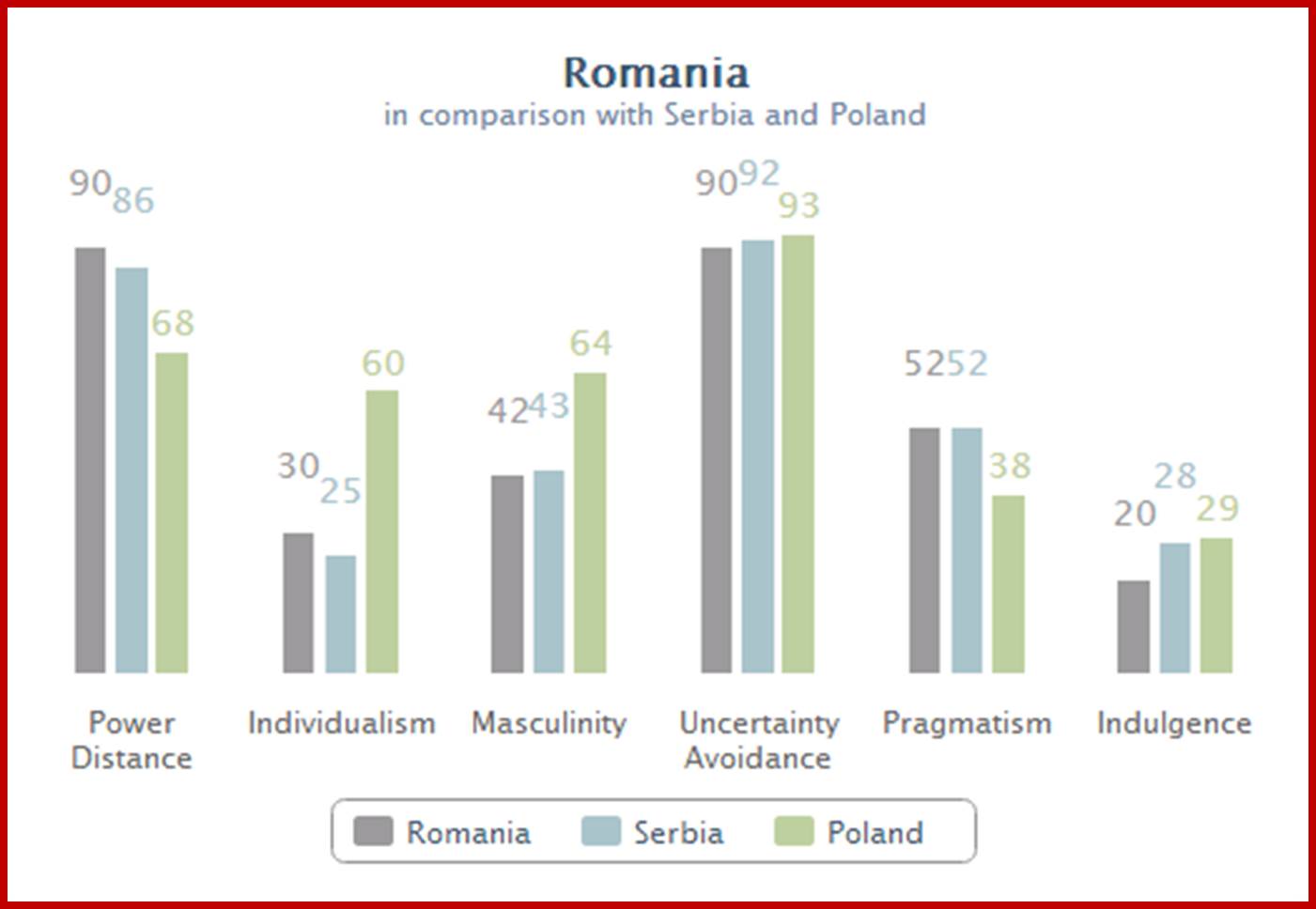

And what about Romania? We chose it because, according to Gallop’s ‘Global Index of Religiosity and Atheism’, it is the most religious country in Europe, with 89% of the population thinking of themselves as religious. The next two European countries for which data is available turn out to be Poland and Serbia, and their scores on the Index are 81% and 77% respectively. What was fascinating was then to discover that the national profiles of these three countries were also remarkably similar:[5] they all scored much higher on Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance than the UK, Norway and the Netherlands, and very much lower on Individualism and Indulgence. So might this spread of characteristics be somehow linked to a propensity to religiosity; and what might this tell us about the prospects for humanism and humanist organisations in such countries?

Anyone carrying out a more rigorous analysis of the factors that make for strong humanist cultures might want to take a closer look at countries with the least institutionalised religious privilege, greatest religious tolerance, liberal legislature, etc. And in this respect we can recommend the International Humanist & Ethical Union’s recent Freedom of Thought Report[6] as a good starting point — the report actually accuses the UK of ‘systematic discrimination against humanists, atheists and the non-religious’ noting that there is an established church; systematic religious privilege; discriminatory prominence given to religious bodies, traditions and leaders; discriminatory tax exemptions; state-funding of religious institutions, including faith schools which have powers to discriminate in admissions or employment, etc. Indeed, the UK is much lower ranked than countries like Jamaica, Niger and Sierra Leone, which are described as ‘free and equal’ — at least in respect of legal discrimination. To be fair, the IHEU does point out that some countries may do better because there is less information about them, or their legislation has not been put to the test.

Anyone carrying out a more rigorous analysis of the factors that make for strong humanist cultures might want to take a closer look at countries with the least institutionalised religious privilege, greatest religious tolerance, liberal legislature, etc. And in this respect we can recommend the International Humanist & Ethical Union’s recent Freedom of Thought Report[6] as a good starting point — the report actually accuses the UK of ‘systematic discrimination against humanists, atheists and the non-religious’ noting that there is an established church; systematic religious privilege; discriminatory prominence given to religious bodies, traditions and leaders; discriminatory tax exemptions; state-funding of religious institutions, including faith schools which have powers to discriminate in admissions or employment, etc. Indeed, the UK is much lower ranked than countries like Jamaica, Niger and Sierra Leone, which are described as ‘free and equal’ — at least in respect of legal discrimination. To be fair, the IHEU does point out that some countries may do better because there is less information about them, or their legislation has not been put to the test.

So Britain has a growing humanist community despite — or is it because of? — ‘systematic discrimination’. Apparently IHEU is looking to include an assessment of cultural discrimination in future versions of the report. We await this with great interest!

Alternative Models of Culture

We have focused in this paper on Hofstede’s 3D Model, but readers might like to explore an alternative (and equally illuminating) model of culture by Richard D Lewis. This one assembles countries into a triangular matrix based on whether people are data-, dialogue- or listener-oriented. According to Lewis we Brits are very definitely ‘data-orientated’, whereas say Southern Europeans and Hispanics are ‘dialogue-oriented’, and people from Asian cultures, ‘listener-oriented’.[7] Quite how MK Humanists would perform on this analysis is hard to know but from the experience of our meetings we would probably turn out to be ‘linear-active’ — we ‘talk half the time’, are ‘polite but direct’, ‘confront with logic’, put ‘truth before diplomacy’ and make ‘limited use of body language’!

Notes

[1] Global Index of Religiosity & Atheism, Win Gallup International Poll, July 2012, http://www.wingia.com/web/files/news/14/file/14.pdf.

[2] National Center for Cultural Competence, Georgetown University, http://nccc.georgetown.edu/

[3] Geert Hofstede, Gert Jan Hofstede, Michael Minkov (2010): ‘Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind’, McGraw-Hill

[4] For a more detailed analysis of the Centre’s ‘Culture Compass Survey’ for the UK to http://geert-hofstede.com/united-kingdom.html

[5] The Hofstede Centre allows you (for free) to compare up to three countries (http://geert-hofstede.com/countries.html)

[6] International Humanist & Ethical Union, Dec 2013.

[7] Richard D Lewis (2005): ‘When Cultures Collide: Leading Across Cultures’, Nicholas Brealey Publishing

Mike Flood is Chair of Milton Keynes Humanists. He works on grassroots development in low-income countries.

This is very interesting Mike, thank you so much for this follow-up work! 🙂

Thanks to Mike for a very clear and interesting article. Hofstede’s work is fascinating but I think it needs to be lined up with similar frameworks to see how the results can be integrated with other data. For example, Shalom Schwarz’s mental map of human values, ranging from self-centred values to biospheric and other-directed ones; Mary Douglas & Michael Thompson’s model of 4-5 different cultural rationalities and dispositions (individualist, hierarchist, fatalist and egalitarian); Ronald Ingelhart’s international values comparisons; etc.

The trouble with ‘humanism’ as a category is that it is not one that many people would self-identify with, even if their explicit and tacit values might tally with your definition; and it is also very capacious. For example, I and many other liberal (and not so liberal) Christians would want to self-identify as Christian Humanists. Not all humanists are secularists, and vice versa; not all humanists are atheists, and vice versa.

The Humanism the BHA is about and which this post refers to is the type which entails a naturalistic worldview, and so isn’t inclusive of theism. There are other ‘humanisms’ out there which mean different things but they’re a very separate topic.