It was a shock last month to find out that the school teacher I remember most fondly had died. It was even more of a shock to find myself organising his funeral.

Tony was a difficult man to define. A magnetic personality, he threw himself into school life with passion and verve, yet it was painfully obvious to many of us that his private life was a lonely one. As someone with virtually no family and with a tendency to push even those that he cared for away, my beloved Classics master was left lying in a hospital mortuary for over a fortnight whilst a solicitor, his sole executor, waited and hoped that a friend or a colleague would come forward for him. For reasons that still escape me, nobody did.

A ritualistic response to death is one of the things that defines us as a species. Tentative evidence of burial or funerary caching goes back to the Stone Age, and it seems clear that our earliest ancestors began interring their dead, sometimes with personal effects. Interestingly, some anthropologists immediately jump to the conclusion that these relics must be evidence for a belief in some kind of afterlife, in which it was assumed that the deceased individual would require the tools of his trade; others are more cautious, and argue that grave goods are simply evidence of individualisation and respect – religious or not, we like to bury a person’s things with them, as symbolic markers of who they were and the impact that they had on the world.

Certainly, everyone that knew Tony would have been acutely aware that he would not have wanted a fuss. I am told that it took some persuading to make him attend his own retirement party, a fact that does not surprise me in the least. However, people still went to the trouble to convince him, and with good reason: retirement parties matter. People want to offer their thanks and to acknowledge the contribution that somebody has made, however much a man like Tony would have waved his hands dismissively and insisted that he had been simply doing his job.

In the same way, but even more so, funerals matter. They matter because someone has lived; they matter because someone has died; they matter because we have to say farewell to their body and, in that inevitable moment, accept that they are gone. ‘People talk about “going through” grief,’ a friend once said to me; ‘the truth is that it goes through you.’ We can’t escape the physical, the visceral nature of loss, and our farewell to the corporeal entity that was once a vibrant individual is a painful but inescapable necessity. For all these reasons, I could not stand by and leave my dearest old teacher’s send-off to the reluctant whim of his legal executor. I simply couldn’t bear it.

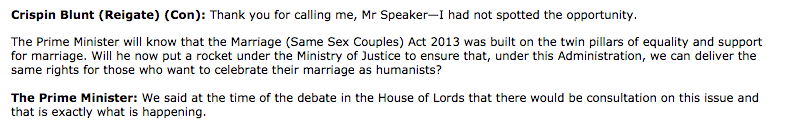

Tony left no instructions, but from my memories of him, one decision was mercifully clear: without hesitation, I asked the funeral director to book a humanist celebrant. Those of you who have read some of my previous articles will know the kind of school that I attended and therefore where Tony worked, an institution shrouded in religious superstition and dogma. Tony had a profound influence on me by modelling informed dissent; this was a man who pointedly read a book in the Chapel services he was obliged to attend, and who summarised religion quite simply as ‘a load of old hooey.’ In a tightly-controlled environment, where religious doctrine ruled and questions were ignored, it was frankly thrilling.

The other decisions I had to make for him were much harder, but I was fortunate to have the proactive support of another ex-pupil. She suggested a poem that she had studied with him, Poem 101 by Catullus, a poignant tribute to his dead brother from which the title of this article is taken; she was willing to read the poem for us in the original Latin, and she did so magnificently. I chose music that reflected Tony’s career as a Classicist, from Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas and from Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice. Who knows what he would have made of it all, but I hoped it was acceptable. I was also lucky enough to have the services of an outstanding Celebrant, accredited by the BHA and meticulous in his approach. Philip Scott drove all the way from Reading to meet me at my place of work in Woking, for he insisted that we must meet in person and not discuss the funeral over the phone. He listened with care and asked searching questions, he chased up the few leads that I was able to give him and ultimately he pieced together a moving yet respectful tribute to a man who was intensely private – a difficult task indeed.

Planning Tony’s funeral with minimal support has been challenging and stressful. There were times when I doubted myself, when I agonised about the decisions that I was making and fretted that I was making the wrong ones. For several nights in a row, I barely slept. But despite all of this, I would do it again in a heartbeat. Tony’s legacy lives on in the lives that he touched and I am just one of so many students that owe him the due honour and respect that he deserves. As Aristotle said, teachers who inspire children successfully should be held in the highest esteem; a parent gives life to a child, a teacher shows them the art of living well.