Star Trek’s wealth of moral and philosophical thought and feeling have led Andrew West and Ellis Collins to name creator Gene Roddenberry a humanist hero.

Andrew West on Gene Roddenberry

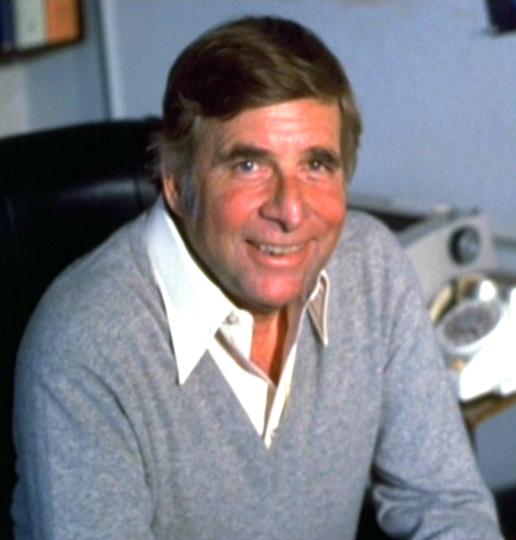

My humanist hero is Gene Roddenberry, the creator of Star Trek and, I think, the most effective communicator of Humanism there has ever been.

For three decades, the universe of Star Trek brought a humanist viewpoint to mainstream audiences. Countless children watched weekly as the galactic Federation of the future was depicted as a philosophers’ state in which the humanist outlook is paramount. It was never hostile to the godly – religion is simply null, and irrelevant. This was never spelt out, because it somehow seems incredibly obvious that the future would be so. It just makes sense. Of course nationality won’t matter in the future. Of course we’ll make sure everyone gets to live to a decent standard. Of course humanity will eventually grow up and out of superstitious thinking. This was unlike anything that had come before. Critics called it a Marxist vision, but one of Gene Roddenberry’s assistants instead described it as Lennonist: a brotherhood of man.

Roddenberry’s quasi-utopian future was attained through the twin humanist beacons of science and moral development. Science fixed poverty with the ‘replicator’ which can make almost anything almost instantly – surely the most desired device in science fiction – while humanity developed a way to bring the disparate races of the galaxy together without coercion or violence. Key to this was the Prime Directive, probably the most vaunted –and most violated – commandment in television. Always problematic, the Prime Directive stated that the Federation must not interfere with other cultures – except of course the Enterprise was forced to intervene in pretty much every episode. This core humanist message was hammered home over the series and the years: people are free to do as they will, but if they need help, you go help.

This optimistic view of humanity’s possibilities was at the core of Roddenbery’s humanism, a life stance he didn’t have a name for when he began questioning religion in his teens. He kept such opinions to himself for years, but came to recognise the power of television to effect social change – both good and bad – and saw an opportunity with Star Trek to bring a non-religious, human-centric philosophy to the general public. He eventually described the show as his ‘statement to the world’.

But his genius was to wrap up all this philosophy in solid entertainment. Morality plays can make for dull television, so Roddenberry blended endearing characters with fantastical situations, cleverly making the resolution of moral conundrums key to the progression of the plot. And in doing so he quietly built a cultural dictionary of philosophy. Want to discuss the limits of artificial intelligence, and what it means to be human? Skip tracts of dialogue and get everybody onto the same page with the name of ‘Data’. The moral culpability of the soldier? The Borg will do nicely. This was never overt, and plenty (including me) were certainly watching for the phaser battles as much as anything else. But ideas etch, and the behaviour of these exciting and civil characters couldn’t help but have an effect. Star Trek always emphasised decision-making, and actually doing something. Every week the Enterprise crew would argue the rights and wrongs of their predicament, before the Captain took it out of the abstract by committing to one side or another, and acting appropriately. There are worse ways to live your life than to bear in mind, ‘What would Picard do in this situation?’.

The conservative nature of 1960s US television didn’t make this easy for Roddenberry, but he ran rings around network censors by setting the stories in space – it’s not about racial equality, silly, it’s about aliens who happen to be different colours. He refused to put a chaplain on the Enterprise, despite regular pressure, and consistently crafted stories about morality that were devoid of moral outrage. Religion is rarely mentioned outright in the original series or The Next Generation, but turns up subtly in the broad, overall themes. In Star Trek: The Next Generation, the only alien with god-like powers is a jerk who hates humanity. But over time he watches humans solving their problems through reason and compassion, despite his offers of magical intervention, and, by the end, he’s won over. It’s hard to see that particular story arc going down well with US networks, so Roddenberry simply didn’t tell them.

But Star Trek went beyond entertainment and subtle dissemination of humanist ideas – it’s not unreasonable to claim that Gene Roddenberry is partly responsible for accelerated pace of modern scientific progress. It’s impossible to know how many children had their sense of wonder stoked by the show, but you can get an anecdotal impression by asking any science graduate if they’re a fan. They probably are. The remarkable correlation between Star Trek fans and scientists may be because the show built upon established knowledge, but pushed it a bit. The ideas weren’t completely out there, so any children interested enough to investigate for themselves wouldn’t be disappointed. They’d discover that warp drives aren’t real, but impulse engines make sense. So why can’t you just use impulse engines to travel around? Because the distances are too great. Wow – just how big is the universe? And what about those communicators that allow the crew to keep in touch on different sides of the planet? Is that possible? Well, no, but radio waves can do that – we just need to figure out how to generate them in something hand-held…

Gene Roddenberry’s humanism affected forty years of children (and adults!), and continues to do so. Generations were raised on a regular diet of secular decency and resolving crises by weighing evidence and listening to all sides. Star Trek lodged abstract philosophy into the public consciousness, and is a pivot around which modern science turns. And above all this, Roddenberry’s vision was a source of hope. Gene Roddenberry brought a hope for humanity to millions, and is a humanist hero for that.

Ellis Collins on Gene Roddenberry

As soon as I started watching Star Trek: The Next Generation, I was hooked. I remember being around nine or ten years old at the time. There was really nothing else quite like it. Here, you had all kinds of Humans – black, white, men, women, some strange people called Klingons and even an Android working together aiming toward the goals – ‘to explore strange new worlds and to boldly go where no one has gone before’. Any problems that happened to occur along the way to these goals and the whole staff would sit down and decide the best course of action, based on two things – reason and logic. It’s easy to see now, looking back at this program, that it was a humanist’s dream.

It took me quite a long time to discover what a Humanist was – I would have been about 20 years old at the time. One late night I was looking through pages among pages of internet information, some of it useful, some not. I happened to stumble across Gene Roddenberry’s Wikipedia page. Scrolling down to Gene’s religious beliefs it stated that he was an ‘agnostic’ and ‘humanist’. ‘A humanist?’ I thought. I really had no clue what this was. A simple click of a button and suddenly I knew, I have to say, it made more sense to me than any other world view I had encountered.

I am 29 years old now. I can honestly say that I truly feel I owe my current outlook and views on life to Gene Roddenberry. If it wasn’t for Gene Roddenberry I honestly don’t know whether I would have got involved in the activities that I like and whether or not I would have learned about some of the most interesting people I could ever learn about, people like Carl Sagan, Richard Dawkins and James Randi to name a few. Upon further research I discovered that Gene had lots of problems just getting Trek onto TV at all. TV executives were very worried about the original series because Gene wanted to include a certain alien with pointy ears and even worse, he also wanted to include a woman on the show – a black one at that. He had to push and push so that he could get his vision of a future society onto TV. A vision of society where there was no superstition, no people dying from things like hunger, no racial or other prejudices but most importantly a world where there was no war, on Earth at least. Another reason why I think so many people took to Star Trek is because Gene always liked to tackle important social issues in the episodes – issues like Slavery, Welfare and discrimination amongst others were all covered many times. Unfortunately Gene died on October 24th 1991, aged 70.

I just want to say thank you Gene, you are solid proof that just one person can change the world for the better.

These posts are part of a series written by members, friends and Distinguished Supporters of the British Humanist Association about their own ‘humanist heroes’.

Andrew West is photographer-in-residence at the British Humanist Association.

Mr Ellis Collins, is 29 from Nottinghamshire. He is currently re-taking his GCSE’s after 13 years hoping to get out a dead end job. He also enjoys Philosophy and Psychology.