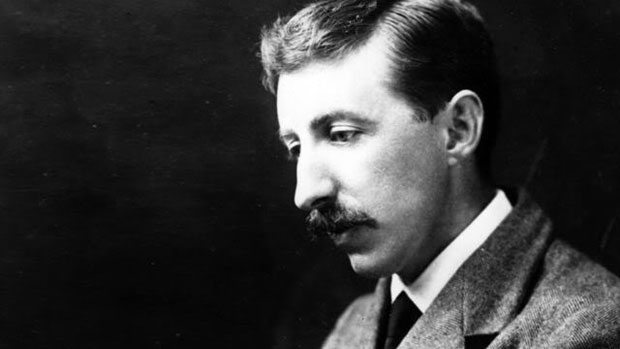

Emily Buchanan explores the pitfalls of modern hyperconnectivity with a look back at two great stories by beloved humanist writer E. M. Forster, as well as film and commentary from the period.

E. M. Forster wrote Howards End and The Machine Stops, and was a key figure in the humanist movement in Britain

Writing at the turn of the twentieth century, E. M. Forster was uncannily aware of our future dependence on technology. In his short story The Machine Stops and in parts of Howards End, Forster explores the notion that technological advance is at the expense of authentic human connection. In a little over 100 years, technology has made our world unrecognisable. But has it, as Forster foresaw, made us isolated and individual, rather than interconnected?

Only connect! That was her whole sermon. Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height. Live in fragments no longer. Only connect, and the beast and the monk, robbed of the isolation that is life to either, will die.

– E. M. Forster, Howards End, 1910

The turn of the century was a time of frenzied advance and rapid rural development. Queen Victoria had just died, kick-starting our modern propensity for progress, and machines had begun to dominate industry and culture. As Forster’s writes in Howards End, ‘month by month the roads smelt more strongly of petrol, and were more difficult to cross, and human beings heard each other speak with greater difficulty, breathed less of the air, and saw less of the sky.’

A state of ‘continual flux’ gripped a society straddling the old and new, and this tension is captured with startling clarity in the social reportage films of Forster’s contemporaries, Mitchell and Kenyon. In particular, a film of Bradford in 1902 shows electric trams sharing streets with horses and carts. If you look closely, ads for familiar brands display the first rumblings of 21st century capitalism and yet the people are timid and formal, every bit the Victorian. This is most clearly exhibited in their overt, often comical reactions to the camera. At the time, a hand-cranked camera would have been an impossibly advanced sight and this is why hoards of delighted children chase the filmmakers up the street and adults gawp at them with a frightened, almost ludditian curiosity. Their mesmerised discomfort is, in itself, mesmerising.

Turn of the century Bradford. Credit: BFI

After all, in the modern day most of us carry a smartphone as if it was an extension of our hand. Technology has been absorbed into every aspect of our lives, affecting our personal relationships, our identities, even our memories. In many ways, our dependence on it means that we have become man and machine, and our access to a world wide web of infinite connectivity has changed our understanding of human connection all together.

Until his death in 1970, E. M. Forster was President of the Cambridge Humanists and a member of the Advisory Council of the British Humanist Association. His humanist principles are at the heart of his writing, so while Mitchell and Kenyon’s footage exposes the condition of Industrial Britain, Forster’s work continues to strive to reconcile that condition with what it means to be human.

In Howards End, this is personified by two London-based families: the Wilcoxes and the Schlegels. The Wilcoxes represent colonialism, social mobility, reason. They are cold, calculated, perfunctory. The Schlegels are literary, sensitive, earthy. They feel that ‘one is certain of nothing but the truth of one’s own emotions,’ and the increasingly fragmented, anonymous nature of London threatens their emotional wellbeing daily.

At the time, Forster felt that Edwardian society was suffering an ‘imaginative poverty.’ Consumerism was thriving and a great monster of a railway had sunk its claws into the British countryside. But rather than connecting humanity, the rail was just another Wilcoxian commodity, taking people from one mechanical city to another – not allowing them to take root in the earth or in each other.

‘Man is an odd, sad creature as yet, intent on pilfering the earth, and heedless of the growths within himself. He cannot be bored about psychology. He leaves it to the specialist, which is as if he should leave his dinner to be eaten by a steam-engine. He cannot be bothered to digest his own soul.’

– E. M. Forster, Howards End, 1910

This ideology comes into its own in The Machine Stops, a dystopian science fiction story about technological dependence. In this world, the toxic smog he vilifies in Howards End has long since suffocated the earth and it is now an uninhabitable wasteland. Each human lives underground inside a single hexagonal cell held within a beehive-like colony. Each cell is controlled by an autonomous computer known as ‘the Machine.’ The people are withered shells of their ancestors and live in total isolation – although the omnipotent Machine connects them to the rest of the world through instant messaging and video calls. It also delivers music, information and all amenities at the touch of a button. Subservience to the Machine is considered an advanced human quality, as is physical weakness, and eventually it is worshipped as god.

A new century, and a brave new world. Credit: BFI

Written in 1909, Forster’s cautionary tale is staggeringly apt in a modern context. He predicts a number of modern technologies, in particular the internet, and in doing so exposes our increasingly problematic relationships with the environment and technology.

‘But Humanity, in its desire for comfort, had over-reached itself. It had exploited the riches of nature too far. Quietly and complacently, it was sinking into decadence, and progress had come to mean the progress of the Machine.’

– E. M. Forster, The Machine Stops, 1909

Whilst Vashti, the main protagonist, is in complete isolation, she is never alone. The Machine connects her to the world and although she can select ‘the isolation knob, so that no one else could speak to her,’ the hum of the Machine is eternal. In fact, when the Machine inevitably stops, the silence kills ‘many thousands of people outright,’ for they have never known ‘the silence which is the voice of the earth and of the generations who have gone.’ Connection is infinite, and Vashti knows ‘several thousand people.’

However, just as Margaret Schlegel remarks in Howards End, ‘The more people one knows the easier it becomes to replace them.’ Too many connections devalues each one in a kind of emotional hyperinflation. For the Schlegels, this is the constant danger of London; for Vashti it is the inevitable by-product of remote communication technology, and something that she has been indoctrinated to approve of.

There are a number of prominent modern parallels here. Today, people tout the benefits of disconnection as if it were an antidote to a social problem. Many of us need to remind ourselves to ‘unplug,’ to select the isolation knob, so that we might be present in the moment, or simply alone, and this is no easy task. For some, disconnection induces anxiety, a fear of missing out, a sense of isolation. So whilst hyperconnectivity is isolating in the way that it denies direct, personal experience, we have to isolate ourselves even further just to get away from it. It’s an absurd paradox.

From the isolation of our smartphone bubble, our hexagonal cell, we can discuss, arrange, meet, read, watch, remember, create, destroy, repair, buy. We needn’t interact on a human level to achieve any of this. As technology becomes more autonomous and the boundaries between reality and technology become blurred, we will lose more direct experience – that fragment of connection that is fundamental to our humanity. In The Machine Stops, Vashti is crippled by ‘the terrors of direct experience.’ She has spent so long connected to the machine that personal interaction has become obsolete.

Autonomous technology only intensifies this risk. It takes away a fundamental aspect of our humanity – the need to think and act for ourselves. In the story, the Machine uses its ubiquity for surveillance and mind control, systematically devaluing every aspect of humanity by rendering it useless through advance. Our ubiquitous technology is already being used for surveillance. Before long, it too could be used to deny us basic human rights.

This degradation of humanity comes to a head in The Machine Stops when Vashti admits that ‘she would sometimes ask for Euthanasia herself. But the death-rate was not permitted to exceed the birth-rate, and the Machine had hitherto refused it to her.’ Although this might seem like an extreme depiction, we are reminded of Anne, the retired art teacher who chose euthanasia just last week because she had ‘grown weary of the pace of modern life’ and of how technology had changed society. Anne, who did not want to give her last name, believed that people were becoming robots attached to their gadgets. ‘They say adapt or die,’ she said, ‘At my age, I feel I can’t adapt, because the new age is not an age that I grew up to understand.’

It is difficult to digest, but the truth is that our society has become a dystopian science fiction of sorts. We are disregarding the plight of our environment in order to advance. We are disregarding our humanity in order to connect. Our devotion to technology is borderline theological and our desensitisation impacts our ability to relate to the natural. We are all well aware of the dangers of that by now. Indeed, the repercussions of the industrial-technological age can already be felt the world over and the more we surround ourselves with a virtual reality controlled by machines that are infinitely smarter than ourselves, the more out of touch we become with the reality of our situation.

Forster felt this stronger than most. His whole ideology rests on ‘the building of a rainbow bridge’ that would reconcile our societal need to progress with our propensity for unconditional love. That latter aspect, although such a primordial compulsion, anchors our humanity and our ability to connect in a way that progresses both man and machine.

‘I am dying – but we touch, we talk, not through the Machine.’

Emily Buchanan is a writer and digital editor living in Norwich. An interest in history and literature lends itself to an affection for long-form content, and specialisms include environmental policy, international affairs and sociology. Emily is a blogger for the Huffington Post, an employability speaker and an aspiring fiction writer. You can follow her on Twitter.

Appendix:

If you enjoyed the above, here is a video of The Machine Stops from Out of the Unknown in 1966. Enjoy!