Several lessons can be drawn from the so-called ‘Trojan Horse’ affair, including

- that religious extremism is completely different from terrorism and that politicians who used the Birmingham schools story for political ends have a lot to answer for

- that we need to watch for hijacking of schools by religious (or any other) extremists for their own religious ends, and

- that the activities condemned in these non-faith schools are exactly what are praised in faith schools

…which must raise questions about faith schools: what is so different about a narrow Jewish or Catholic ethos and curriculum from what devout Muslim governors were trying (admittedly unlawfully) to impose on their Birmingham schools?Politicians like Liam Byrne use this last point to argue that maybe these schools should be converted to faith schools so as to legitimise what they are doing: one moment what Park View school does is deplorable, the next it is spot on. But this reminds us that the whole debate about faith schools is marked with dishonesty by their defenders.

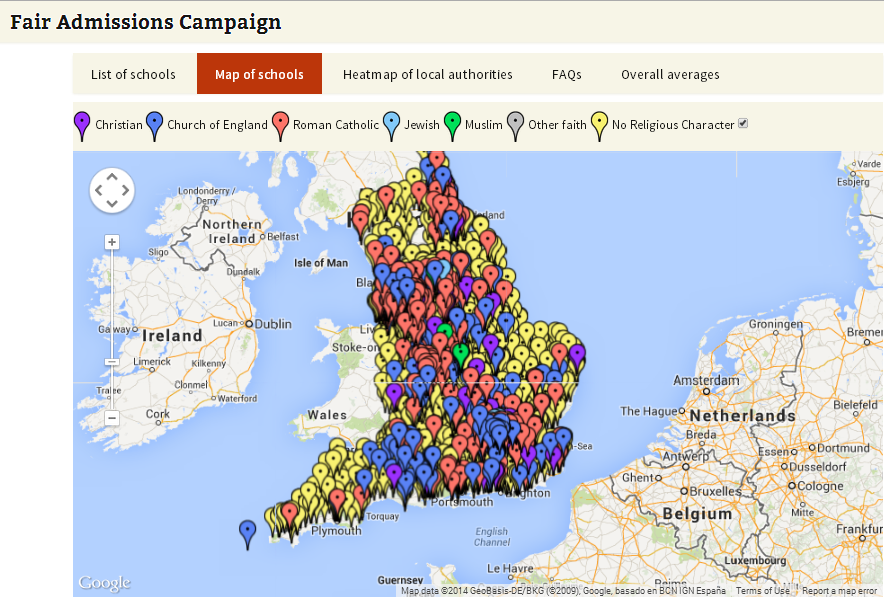

The research is clear – ‘faith’ schools are more socio-economically compared to the local average. Pictured: the Fair Admissions Campaign website.

When the Fair Admissions Campaign shows indisputably that religious schools discriminate in their admissions against poorer families (as measured by eligibility for free school meals), the Catholic Education Service uses phony stats to fend off the criticism. When the BHA tweets that if people are worried about the intense religiosity of the Birmingham schools, they should pay attention also to faith schools, the Church of England’s PR man the Rev Arun Arora treats this one tweet as the sum of BHA policy and writes a column ridiculing us, whereupon friendly columnists echo him in their own names.

The Church of England in public defends its schools with a pretence of selfless service to the general interest while in private pursuing an aggressively expansionist policy as its last hope for survival, using the bait of places in its schools to induce parents into church.

But these sponsors of religious schools paid for from the public purse and the politicians who defend them are guilty also on another count: their refusal to engage with the arguments of principle in favour of reform.

In this they differ from many proponents of Jewish or Islamic schools – before learning to be more circumspect, Ibrahim Lawson said on Radio 4 that the purpose of his Nottingham school was indoctrination. The churches do not admit that their real aim is to recruit a new generation to join their congregations. That they enjoy limited success, that some Anglican schools are largely full of pupils from Muslim families, that they often provide a good education, that their version of indoctrination is subtle and muted – these are mitigations but not answers to the principled objection to faith schools that they do not respect the autonomy of children and their own rights under the Convention on the Rights of the Child to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.

Defenders quote against this the European Convention on Human Rights that ‘the State shall respect the right of parents to ensure such education and teaching in conformity with their own religions and philosophical convictions” — and this is indeed a necessary defence against an over-mighty state imposing a totalitarian education on everyone. But the Convention does not help them: it protects the private or joint endeavours of parents but it does not require the general public to finance churches in their self-promotion.

Nor do the churches face up to the implications of public finance for denominational schools in an age of human rights and non-discrimination. If Catholic schools, why not Muslim and Hindu? If Anglican, why not Buddhist and Sikh? or Seventh Day Adventist? or schools to propagate the teachings of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi? Or indeed Steiner schools based on their founder’s racist and anti-science writings? All these now feature in the publicly funded school system. Supporters of Church of England schools now have to defend also these more dubious enterprises.

But our arguments of principle go beyond objecting to indoctrination of children. These schools are inevitably divisive, and they increasingly balkanise the population. They are a relic of the sort of divisive multiculturalism that was such a mistake of the Blair government. Time and again it has been shown that it is necessary only to divide people into groups for them to form loyalties and hostilities, and when the divisions are based on rival religious claims they are all the more dangerous. It is no answer that these divisive schools have occasional visits to each other – children need to be educated alongside each other every day, to learn about and from each other, not to be thrown into occasional artificial encounters.

But do not expect the churches to provide a defence on principle of religious schools any time soon.