The numbers are in (and have been for a while). Can politicians really keep insisting this is a ‘Christian country’? Photo: Chris Combe.

Elected officials to this day continue to cite the Census to make the point that Britain is a ‘Christian country’ or a country made up principally of Christians. The Census statistic of 59% is used to justify all sorts of privileges granted to the religious in Britain today, including the widespread handing over of public services and schools to religious control and the place of unelected bishops in our legislature, not to mention the recurrent exceptionalising of Christian contributions to our shared cultural life. But is that statistic true? Is it any good?

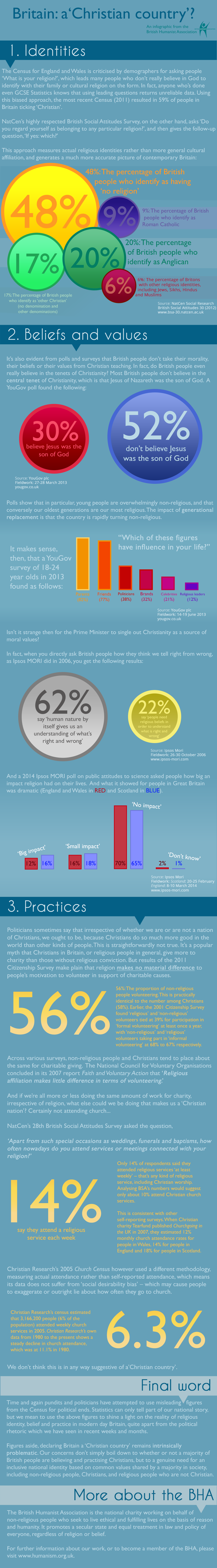

The likely answer is no, and any demographer can tell you why. By asking the leading question ‘What is your religion?’ in the context of a series of questions about ethnicity and cultural background, the Census leads to higher numbers of people identifying themselves with their family or cultural religious background, and for the most part not with that they actually believe, feel they belong to, or practise.

The Census statistic is used to justify all sorts of privileges granted to the religious in Britain today. But is it any good?

Most other rigorous surveys will tell you a different story – the story of a very diverse Britain united for the most part by common values which straddle the ‘religious divide’. The most recent of these surveys was by YouGov this April, and it found that around two thirds of Britons, when asked, would say they are ‘not religious’.

The April poll, commissioned by the Sunday Times, asked the question ‘Would you describe yourself as being a practicing member of a religion?’ and found that 62% of the general public said ‘no’. Christianity polled as the second most popular option, accounting for 33% of the public. And it’s by no means a one-off. Most polls of the last decade have given very similar results.

This majority ‘not religious’ figure has been found repeatedly in recent years. A recent example of this trend is the Survation poll last November, which asked ‘Do you consider yourself religious or not religious?’ and found that 60.5% of Brits are the latter. These figures are in turn consistent with year-on-year polling from the British Social Attitudes Survey, which finds that around or slightly over half of the population is in fact non-religious (and that 42% Brits identify as Christian) when it asked ‘1. Do you regard yourself as belonging to any particular religion? 2: If yes: which?’. A YouGov poll in April 2014 also found that 50% of Brits were non-religious, and that three quarters of the population were ‘not religious or not very religious’. Very similar results in 2011 and 2012, and numerous others, overwhelmingly reinforce the pattern.

We can say with some confidence that half of Brits are non-religious

Equally, the one third figure for believing Christians has been found time and time again. A YouGov poll for the Times in February this year found that only 55% of British Christians ‘believed in God,’ bringing the total proportion down from 49% of Britons who say they are Christian to around 23% for ‘Christians who believe in God’. A 2013 YouGov poll which asked how many people in Britain believed in the central tenet of Christianity – that Jesus of the Nazareth was the son of God – found a figure of 30%. It’s that same figure again – around a third

In most aspects of their jobs, politicians look closely at these sorts of surveys when making policy decisions, or when attempting to win over new voters with popular initiatives. They know, and statisticians can tell you why, that the margin of error on these things is usually around 1-3%. So I feel we can say with some confidence that half of Brits are non-religious (only 4% of ‘nones’, according to the Times/YouGov 2015 poll, ‘believe in a god’) and that beyond that, two thirds are ‘not religious’ – in the sense of not seeing religion as very important or not practising. It’s a widespread trend: only 30% of Brits are believing Christians, and only 6% or fewer Brits go to church on a given Sunday.

Much more importantly, three quarters of Brits say they are opposed to public policy decisions being influenced by religion

The Census result would suggest that three quarters or more of Brits, cutting across the religious divide, would cite some sort of Christian cultural background, but this is a broad group indeed – both Justin Welby and Professor Richard Dawkins would say they are culturally Christian! Much more importantly, three quarters of Brits say they are opposed to public policy decisions being influenced by religion – with 92% of Christians agreeing that the law should apply equally regardless of religion.

Politicians trotting out the old Census figure to justify handouts or, engaged in cynical vote-grabbing, should remember that most of us want to be treated equally and want a level playing field – including by opposing ingrained religious privilege, such as by opposing ‘faith’ schools and bishops in the House of Lords. Of course, politicians are not won over by opinion polls alone, and most are wary of the power of religious institutions, whose views tends to be a bit more traditional than those of their flocks. But change is inevitable, and on the way – the fact that the next generation rising through the ranks is overwhelmingly non-religious could well promise to erode the power of churches over our elected representatives.