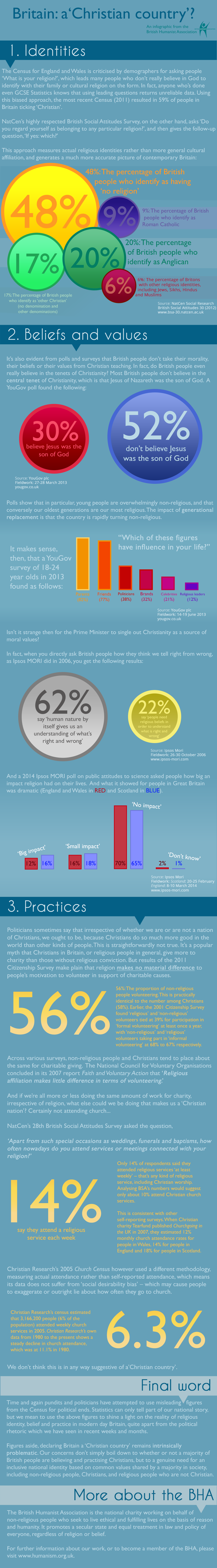

Last Monday the British Humanist Association coordinated an open letter, signed by more than 50 public figures, including authors, scientists, broadcasters, campaigners and comedians, who wrote to the Prime Minister to challenge his statement that Britain was a Christian country.

The story dominated the news agenda for the past week, and today the BHA has released an infographic which compiles statistics on the current state of religious identity, belief, and values in contemporary Britain. You can view the graphic below: