On Monday, when the documents related to the Ofsted and Education Funding Agency investigations in Birmingham were published and Michael Gove made a statement in the House of Commons about it, we tweeted approvingly when Crispin Blunt MP raised the issue of ‘faith’ schools more generally:

Great from @crispinbluntmp – there should be no faith schools, every school should prepare pupils for life in wider British society

— Humanists UK (@Humanists_UK) June 9, 2014

Arun Arora, Director of Communications for the Church of England, took this single comment and spun it into a baseless article alleging that the British Humanist Association had tried to turn the whole situation in Birmingham into a debate about ‘faith’ schools and attacking the notion that it lends itself to wider comments of this nature. He pointed out that none of the schools involved in Birmingham are legally designated as religious, and that Church of England schools do not face similar issues.

This response completely misrepresents the reason why ‘faith’ schools are relevant to this debate. We never said any of the schools in Birmingham are religious and in fact we have continually drawn attention to the fact that they are not.

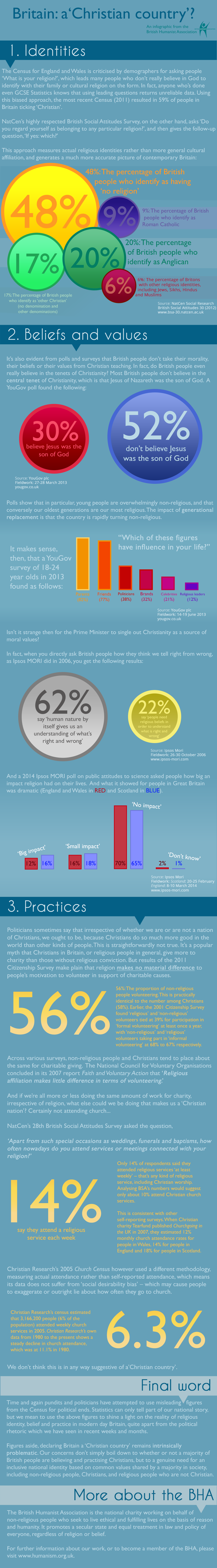

The reason why all ‘faith’ schools are relevant to this debate is not because Church of England schools foster extremism – they clearly don’t, and for Arun to base a whole article on the idea that we think they do is bizarre. There have been articles across from publications across the political spectrum discussing the place of ‘faith’ schools in response to the situation in Birmingham. Even the Secretary of State himself, in his response to Crispin Blunt, said that ‘In the light of what has been revealed, it is important to have a debate about the proper place of faith in education’. The Shadow Secretary of State has made similar comments; it is clear that such a discussion has relevance and that to endorse that claim is not to imply in anyway that any of the schools in Birmingham recently investigated were religious ones.

What the existence of Church of England schools plainly does is support the mentality that some state schools are for Anglicans, some are for Catholics, some are for Jews… and of course, given this mentality, we are going to arrive at a situation where some Muslims start seeing certain schools as ‘Muslim schools’, whether those schools are legally designated as Islamic or not. We can only prevent the type of problem we saw in Birmingham from occurring and spreading – and stop segregation between different schools – if we work to get away from the whole notion that different state-funded schools belong to different religious communities.

If we do not do this then we will continue down the path we are on of further segregation between schools along both socio-economic and ethnic grounds. Ted Cantle wrote the main reports into the 2001 race riots, and identified segregated schools as a cause of those riots. The fact that he believes this country’s schools are far more segregated now than they were when the 2001 race riots occurred is shocking.

We welcome any public debate around the place of religion in education that has been happening since Monday. It is right that the public asks questions about the fact that most of the one third of state-funded schools that are religious – including many Church of England schools – are allowed to turn children away who live across the road but whose parents are of the wrong religion or no religion; are allowed to pick the staff they hire on the basis not of their teaching ability but of their faith; and are allowed to teach a curriculum that proselytises a certain religion and dismisses all other worldviews. Surveys show that all of these practices are hugely unpopular with the public at large.

That official representatives of the Church of England wish to stifle that debate seems self-interested at the very least.