David Cameron is looking right at the problem, but choosing to ignore it. Photo credit: The Prime Minister’s Office/Creative Commons license.

The Prime Minister’s speech on extremism on Monday has received a mixed reaction; unsurprising given the sensitivity and complexity of the issue. However, as is so often the case, the mixed reaction was also at least in part a result of mixed messages. Specifically, the praise that should have been provoked by Cameron’s admirable emphasis on the need to tackle segregation in our education system was tempered by his contradictory reaffirmation of support for ‘faith’ schools.

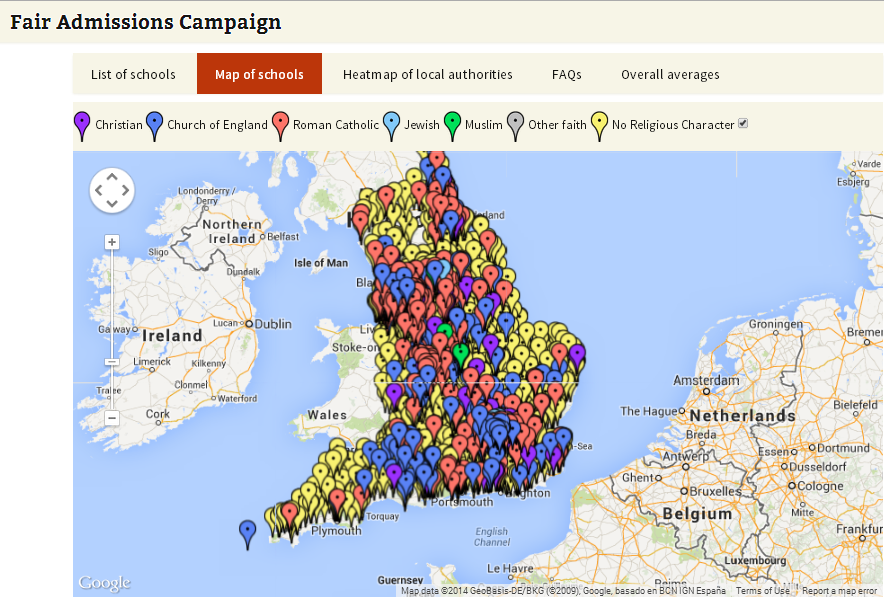

The response of successive Governments to the increasing religious and ethnic diversity of the UK has been to provide more ‘faith’ schools, of more kinds, to cater for these different groups. In 1998 there were 24 state-funded Jewish schools, and no Muslim, Sikh or Hindu schools. In 2015, there are now 48 Jewish, 21 Muslim, 10 Sikh and 5 Hindu state schools, and growing. More children of all religions are being educated in ‘faith’ schools now than ever before.

There are many, the British Humanist Association among them, who are absolutely convinced that this approach to building a multicultural society will be remembered as one of the most ruinous and damaging to the fabric of our communities and our society that has ever been pursued. It is an approach which is impossible to fathom.

Presented with the challenge of integrating a complex mix of religions, beliefs, ethnicities, and social backgrounds into one cohesive society, we have two options. The first option is to continue with an education system which divides children in almost all imaginable ways. ‘Faith’ schools segregate along religious lines, along socio-economic lines, and along ethnic lines – the evidence for this is clear. This first option therefore involves accepting this sorry starting point and then working round the clock to think of ways to get these different groups to interact with and understand one another (Shared facilities and integrated teaching being the Government’s latest proposals).

The second option is simple. We make all schools inclusive, we bring all children together, we ensure that it is their similarities that are celebrated and which become ingrained in them, rather than their differences, and then we sit back and watch while all our work is done for us.

Regrettably, this is not the option that has been taken.

In his speech, the Prime Minister referred to the policy introduced under the Coalition Government of only allowing new ‘faith’ academies and free schools to allocate half their places on the basis of faith. That development was to be welcomed, but it didn’t go nearly far enough. More than a third of state-funded schools in England and Wales – over 7,000 schools – are religious schools and only a small proportion of these are free schools. Clearly no religious selection at all would be preferable, but it is equally important to remember that discussions about religious selection should not detract from the fact that whether religiously selective or not, ’faith’ schools are inherently exclusive.

That is why Cameron’s expression of hope that ‘our young people can be the key to bringing our country together’, immediately preceded by a promise that he will not seek to ‘dismantle faith schools’, was so disheartening.

One has to ask, how we can expect our children to create the inclusive, integrated and cohesive society that we have thus far been unable to achieve, if we continue to define them and divide them by the religions and beliefs of their parents?

When it comes to tackling segregation and promoting integration, there is clearly no silver bullet. The process is difficult and there’s a long way to go. You can be absolutely sure, though, that an end to ‘faith’ schools and an end to the division they foster, is the closest thing to that silver bullet we have. If only our Prime Minister wasn’t so gun shy.