With the news replete with stories of humanists and freethinkers killed and persecuted for ‘blasphemy’ around the world, Alex Sinclair-Lack asks ‘How candid can I be about my beliefs’?

Amman’s Citadel in Jordan. Photo by Alex Sinclair-Lack.

All humanists must grapple with the question of when it is appropriate to tell people that you don’t believe in their god, and when, if ever, you might choose to hide your beliefs for fear of causing offence. Across the atheist spectrum there is strong disagreement about how to approach these issues. At one extreme, there are those who keep their beliefs completely hidden. At the other, we have keyboard warriors with an uncanny ability to turn the YouTube comment sections of pop videos and cookery guides into pseudo-theological, venomous outpourings about the failings of the Catholic Church. Frankly, I have a little sympathy for both. However, the dilemma I describe becomes more apparent and important in highly religious countries. During a six-month stay in Amman, Jordan, I discovered my own answer to the question.

Having found comfort and confidence in

shared values of compassion. I made the conscious

decision to tell people of my lack of faith.

As a liberal and a humanist, I had reservations about moving to a Middle Eastern country. I was pleasantly surprised to discover that Jordan does not share many of the intolerances of the surrounding nations. In fact, it blows many perceptions of the region out of the water. Surrounded by Iraq, Israel, Syria and Saudi Arabia; Jordan has remained peaceful, safe, and welcoming. While the UK Parliament pats itself on the back for having voted to let in a couple of hundred child refugees, Jordan was taking them in by the million. It is worth noting that King Abdullah II does this in spite of a devastating water shortage because he considers it Jordan’s moral duty to help refugees regardless of nationality and religion.

Having found comfort and confidence in shared values of compassion, I made the conscious decision to tell people of my lack of faith. At first to Jordanian friends, and then to colleagues, and eventually to inquiring strangers. The inquiry comes up more often than you might expect. Reactions ranged from sheer horror, to intrigue, to nonchalance. My personal favourite occurred during filming for an unfinished pet project, a documentary short: Syrian Santa. It was centred on a young Muslim refugee working as Father Christmas in a mall, who when I asked him if my non-belief offended him, replied: ‘Oh please, all of my friends are atheists!’

A multi-faith mural in Jordan. Photo by Alex Sinclair-Lack.

Questions usually followed, and I was happy to answer. Each Q&A session reassured me that these conversations were valuable. This is not because I had any intention of ‘proselytising’ or ‘converting’ or whatever the non-religious equivalent is (de-proselytising, perhaps). Any attempts to convert Muslims or hurt ‘Muslim feelings’ would have landed me a three-year prison sentence. But far more importantly, because it is not my business as a guest of the country to even be considering such an act. I have as little desire to proselytise as I do to be proselytised. My interest lies in conversation not conversion.

Any discussions of faith should be treated with sensitivity and cultural awareness, otherwise they are not only disrespectful and neo-colonial, but counter-productive. I will never preach my beliefs, but I will happily engage with those who are willing. When my admission was met with a grimace, I would follow up with, ‘I realise that atheists do not have a good reputation, but I welcome any questions about my beliefs, if you are interested’.

Reasonable people from all belief systems are keen to understand how non-believers come to ethical decisions and agree that discussion is valuable

The very act of having a friendly conversation…

goes a long way to combating prejudice.

Firstly, the discussion counters widespread misconceptions about what it means to be an atheist. For most people, I was the first openly atheistic person they had encountered. Although my ex-partner might disagree, I like to think that I don’t match up to the idea of an atheist as a nihilistic, ethically reprehensible sinner with a black hole where my heart is meant to be. The very act of having a friendly conversation with a well-meaning, open, and non-pushy non-believer goes a long way to combating prejudice.

Secondly, just by opening a dialogue you create a safe space for other people to explore their own doubt or scepticism, but who are unlikely to have had the same freedoms you have had. This is more likely than you might think. According to a 2012 WIN/Gallup poll, 18% of people in the Arab world consider themselves ‘not a religious person’. That is the equivalent of 75 million people. The percentage rises to as high as 33% in Lebanon and perhaps even more surprisingly, 19% in Saudi Arabia. Even if you do not meet these people directly, you may indirectly inspire tolerance towards them. And there is a reasonable chance you will have enough influence on someone to make them consider before jumping to harsh judgement and disownment. Atheists and agnostics within highly religious countries have one hell of a trail to blaze. What I am advocating is recognising your privilege and using it to help their journey run a little smoother.

I’m not supporting walking around the holy land with an ‘I love Richard Dawkins’ t-shirt. I only had this conversation when I was somewhat confident that I was safe. I would not be so brave as to openly discuss it in Bangladesh or Saudi Arabia, where the price of standing up for non-belief has been such a tragic one. In at least thirteen countries, atheism is punishable by death. And in these countries, the bravery and dangers faced by activists fighting to protect their right to non-belief is not to be compared with anything I will ever encounter. Nor would I be naive enough to claim that everyone has the luxury to speak so openly about non-belief. But it is recognition of that privilege that motivates me. I have been lucky enough to grow up in a society where I am free from these dangers; most people are not.

Use your wits and your intuition, when you feel unsafe, keep your views to yourself. Check the Freedom of Thought Report before you visit any religious country and only do what you feel comfortable with. Given an opportunity, atheists who live with the privilege of safety have a responsibility to detoxify the debate for those that don’t. For me, it is a risk worth taking. Some of my most humbling experiences were when Jordanian people were telling me that I had helped them combat their prejudices. All humanists have a small part to play.

Alex Sinclair-Lack is a writer with an appetite for travel. You can follow his writing and his exploits on Twitter at @alexsinclair.

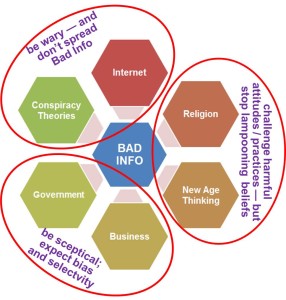

Be vigilant – make sure that ‘a little red light’ comes on in our head whenever you get near to an ‘intellectual black hole’ so that you don’t get sucked in / fall victim.

Be vigilant – make sure that ‘a little red light’ comes on in our head whenever you get near to an ‘intellectual black hole’ so that you don’t get sucked in / fall victim.