One third of state-funded schools in England are legally designated with a religious character. Here are ten facts about what that means.

1. Most don’t have to teach about other religions in Religious Education

The majority of ‘faith’ schools are required to teach religious education ‘in accordance with the tenets of the religion or religious denomination’ of the school. In other words, it’s up to the religious body as to what is taught (or not taught) in RE and if a school just wanted to teach about one religion only then it can legally do so. This is compounded by the fact that ‘faith’ schools have an exemption from the Equality Act 2010 when it comes to the curriculum and also the fact that their RE provision is not directly inspected by Ofsted (see no 4 below).

To be more specific, there are two ‘models’ of ‘faith’ school – the voluntary aided model and the voluntary controlled model. Religious Voluntary Aided schools, Free Schools and sponsored Academies follow the voluntary aided model while religious Voluntary Controlled and Foundation schools follow the voluntary controlled model. Religious converter Academies stick to the model they followed prior to conversion.

Over three fifths of ‘faith’ schools follow the voluntary aided model (including all Catholic, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu and Sikh schools and about 45% of Church of England primaries and 70% of Church of England secondaries). Only some Church of England, Methodist and generically Christian schools follow the voluntary controlled model.

Schools with no religious character and those religious schools following the voluntary controlled model must follow an RE syllabus that ‘reflect[s] the fact that the religious traditions in Great Britain are in the main Christian whilst taking account of the teaching and practices of the other principal religions represented in Great Britain.’ But as we said at the start, schools following the voluntary aided model can teach faith-based RE.

In our experience most ‘faith’ schools do teach about other religions – although we do occasionally see exceptions. And non-Anglican/Methodist ‘faith’ schools do often offer GCSEs that only include modules on their particular faith, for example a Catholic theology GCSE or a GCSE only studying Islam.

2. When they do teach about other religions, they often don’t teach about them properly

Following on from the previous point, there is no requirements attached to how exactly RE is taught. Recent Government guidelines on RE such as the 2004 subject framework and the 2010 guidance are non-statutory but at any rate are targeted at schools with no religious character and those following the voluntary controlled model not the voluntary aided model. The RE Council’s 2013 curriculum framework does say that ‘all types of school need to recognise the diversity of the UK and the importance of learning about its religions and worldviews, including those with a significant local presence’ – but again this is non-statutory and the guidance is primarily not for schools following the voluntary aided model.

Instead what ‘faith’ schools following the voluntary aided model can do is teach that the faith of the school is literally true and that all other beliefs are false. Indeed, the 2013 framework says that ‘The REC recognises that in schools with a religious character, there is likely to be an aspiration that RE (and other aspects of school life) will contribute to pupils’ faith development.’

Furthermore, in its policy document Christ at the Centre the Catholic Education Service says ‘The first key reason why Catholic schools are established, then, is to be part of the Church’s mission in education, to place Christ and the teaching of the Catholic Church at the centre of people’s lives. “Education is integral to the mission of the Church to proclaim the Good News. First and foremost every Catholic educational institution is a place to encounter the living God who in Jesus Christ reveals his transforming love and truth.”[Pope Benedict XVI, 2008] This evangelising mission is exercised through the diverse interaction of Catholic schools with their local parishes, families, societies and cultures they serve.’

And the Church of England has produced two major reports on its schools this century – the Dearing Report and the Chadwick Report. The 2001 Dearing Report says that ‘The Church today still wishes to offer education for its own sake as a reflection of God’s love for humanity. But the justification for retaining and aspiring to extend its provision, as recommended in this report, cannot be simply this, when the state is willing to provide as never before and when there are so many calls on the Church’s limited resources. It is, and must be, because that engagement with children and young people in schools will, in the words of the late Lord Runcie when he was Archbishop of Canterbury, enable the Church to: “Nourish those of the faith; Encourage those of other faiths; Challenge those who have no faith.”’

Meanwhile the 2012 Chadwick Report cites as a ‘key premise that appl[ies] equally to children of the faith, of other faiths and of no faith’ to ‘Work towards every child and young person having a life-enhancing encounter with the Christian faith and the person of Jesus Christ’.

3. They don’t have to teach about non-religious people and beliefs

Following on from the fact that schools following the voluntary aided model don’t have to teach about other religions, similarly they don’t have to teach about non-religious beliefs either.

Actually many schools with no religious character don’t do this either. We think that equality and human rights legislation means that the legal requirement for RE syllabuses to include Christianity and ‘other principal religions’ also means that the syllabuses should include non-religious worldviews as well. This is increasingly common and the 2013 RE curriculum framework put non-religious worldviews on an equal footing to the principal religions. When such a high proportion of young people are not religious, this inclusion is vital. But at the same time, some areas such as Birmingham refuse to include any teaching about non-religious beliefs in their syllabus (other, perhaps, than purely to act as critiques of religions).

Turning to ‘faith’ schools, our experience is that many Church of England schools do include non-religious worldviews – particularly where those schools decide to teach the same RE syllabus as is taught in local schools with no religious character, for example in the Diocese of Wakefield.

But a number of CofE schools and many others too do not include teaching about non-religious worldviews in their own right, perhaps only including them as challenges to religion(s) or not including them at all. We have already quoted the Church of England’s Dearing Report setting out Anglican schools’ aim to ‘challenge those who have no faith’. Against this backdrop it is hard to argue that such schools teach about non-religious beliefs properly.

4. Their RE teaching isn’t even inspected by Ofsted. The religious bodies inspect it themselves

Schools are inspected under section 5 of the Education Act 2005. But this says that ‘An inspection which is required under this section must not extend to— (a) denominational education, or (b) the content of collective worship which falls to be inspected under section 48.’

In other words, faith-based education of the sort given in schools following the voluntary aided model is not inspected by Ofsted. Instead, as section 48 of the Act specifies, it is inspected by ‘a person chosen… by the governing body’. In practice this means dioceses for Church of England, Roman Catholic and Methodist schools, and for other faiths it is typically the relevant national religious organisation. What is more, the state pays the religious body to carry out these inspections.

For Anglican and Methodist schools, the inspection is carried out under the ‘SIAMS’ framework. One question asked is ‘How effective is the Religious Education? Within the context of a distinctively Christian character’. This does include a grade descriptor asking ‘To what extent does RE promote community cohesion through an understanding of and respect for diverse faith communities?’ But non-religious beliefs are not included and another grade descriptor asks ‘To what extent does RE promote the distinctive Christian character of the school?’

When Ofsted inspects ‘faith’ schools following the voluntary aided model it will sometimes look at RE lessons as part of its overall assessment of teaching and learning – so in this sense the subject can be indirectly looked at. But it does not inspect or report on the subject specifically (indeed such schools were explicitly excluded from the last subject-specific report on the basis that ‘separate inspection arrangements exist’) and would not mark a school down for teaching from a faith-based perspective or failing to include non-religious beliefs.

5. ‘Faith’ schools do not have to provide much in the way of sex education and can choose to only teach abstinence until marriage

There are very few requirements on any schools in terms of what they must teach about sex education. Maintained schools (i.e. state schools other than Academies and Free Schools) have to follow the national curriculum, which in Science includes puberty and the biological aspects of reproduction. Maintained secondary schools also have to, at a minimum, teach sex education that includes education about sexually transmitted infections, HIV and AIDS. But beyond that there are only requirements to have regard to guidance on the matter and to publish policies.

And Academies and Free Schools only have to have regard to guidance.

This means that a school could, if it wishes, choose to take an approach of only teaching an abstinence until marriage, instead of providing full and comprehensive sex and relationships education that includes teaching about relationships, consent, the advantages of waiting for sex, contraception, abortion and issues related to sexual health other than STIs. The evidence shows that full and comprehensive SRE is what leads to the best outcomes in terms of ensuring that relationships are consensual, preventing unwanted pregnancies, preventing abortions and preventing STIs. So taking an abstinence only approach is unhelpful.

We regularly hear from people who say that they were taught through an abstinence only approach. We also occasionally see issues with respect to religious schools’ approach to teaching about abortion, contraception, sexual orientation and same-sex marriage.

6. Some religious schools have extremely complex admissions policies

The School Admissions Code says that schools must not ‘give priority to children on the basis of any practical or financial support parents may give to the school or any associated organisation, including any religious authority’ or ‘prioritise children on the basis of their own or their parents’ past or current hobbies or activities’. However many high profile ‘faith’ schools have this year been forced to change their admissions policies after taking into account activities such as ‘Bell ringing’, ‘Flower arranging at church’, ‘Assisting with collection/counting money’, ‘Tea & coffee Rota’, ‘Church cleaning’, ‘Church maintenance’, ‘Parish Magazine Editor’ and ‘Technical support’.

In fact the Catholic Diocese of Brentwood’s priest’s reference form asks parents, ‘If you or your child participate or contribute to parish activities, you may wish to indicate below.’ In other words, every Catholic school in the diocese is currently gathering examples of this kind of activity. This breaks the Code either because it is being taken into account or because it is being asked about needlessly.

Furthermore, since the London Oratory School was told to remove its ‘Catholic service criterion’ (where parents could get two points towards entry for three years of activities such as flower arranging) there has been a looming threat that the school will judicially review the decision.

Meanwhile, one Jewish girls’ school in Hackney specifies that ‘Charedi homes do not have TV or other inappropriate media, and parents will ensure that their children will not have access to the Internet and any other media which do not meet the stringent moral criteria of the Charedi community. Families will also dress at all times in accordance with the strictest standards of Tznius (modesty) as laid down by the Rabbinate of the Union of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations.’ – before giving priority in entry to ‘Charedi Jewish girls who meet the Charedi criteria as prescribed by the Rabbinate of the Union of Orthodox Hebrew Congregations.’ This doesn’t seem to us to be a sensible basis on which to decide who does and does not gain entry to a state funded school.

7. They can turn down children whose parents don’t share the school’s religion, no matter where they live

‘Faith’ schools that are voluntary aided, foundation, Academy or Free Schools set their own admissions policies, whereas voluntary controlled schools have their admissions policies set by their local authority. Again they have an exemption from the Equality Act 2010 when it comes to discrimination in school admissions. The result is that many schools can – and do – give preference to those of a particular faith over others in their admissions. They can only do this if sufficiently oversubscribed, Free Schools can only do so for up to half of places, and only about a quarter of local authorities allow some of their Voluntary Controlled schools to select.

Last year the Fair Admissions Campaign looked at the admissions policies of every religious secondary school in England. In total it found that 99.8% of places at Catholic schools, 100% of places at Jewish schools and 94.9% of places at Muslim schools were subject to religious selection criteria. At Church of England schools only 49.7% of places were subject to such criteria – but if you only focus on CofE schools that are in no way selected in terms of how much they can select (for example because they are VC schools) then the figure rises to 68%.

In total the Campaign estimated that some 1.2 million places are subject to religious selection criteria. This is a quarter more than the number of places in grammar, private and single-sex schools combined.

The problem is particularly acute in some parts of the country. For example, in Kensington and Chelsea, some 60% of secondary places are religiously selected. In Liverpool it’s around half.

8. Priority is often given to other religions over the non-religious

In our experience, a typical Catholic school priority list goes:

1. Catholic

2. Other Christian

3. Other faith

4. Distance from school – which, of course, means non-religious people.

That schools are allowed to prioritise those of other faiths over others is justified on the basis that ‘It would, for example, allow a Church of England school to allocate some places to children from Hindu or Muslim families if it wanted to ensure a mixed intake reflecting the diversity of the local population.’ However, this kind of admissions policy is extremely rare in practice. Much more common is putting those of no religion below those of religions other than that of the school. Voluntary aided model Church of England schools also frequently engage in this practice.

9. Most ‘faith’ schools can require every single teacher to share the faith of the school

The Equality Act 2010 has provisions that prevent discrimination by employers against employees. But there is an exemption from the Act to allow ‘faith’ schools, uniquely, to discriminate much more widely. In the case of those three-fifths following the voluntary aided model, this means that every single teacher can legally be required to share the faith of the school. For the rest it means for up to a fifth of staff.

How much does this happen in practice? Catholic schools are an interesting case in point. The Catholic Education Service’s stats show that not every teacher in a Catholic school is a Catholic. But their standard teacher application form asks applicants to give their ‘Religious Denomination / Faith’, adding ‘Schools/Colleges of a Religious Character are permitted, where recruiting for Teaching posts, to give preference to applicants who are practising Catholics and, therefore, one [referee] should be your Parish Priest/the Priest of the Parish where you regularly worship.’

And in their policy document, the CES says that ‘Preferential consideration should… be given to practising Catholics for all teaching posts and for non-teaching posts where there is a specific religious occupational requirement, i.e., chaplaincy post. In England and Wales statutory provision allows for such preferences to be made.’ In other words, the advice is that Catholic schools should only hire non-Catholics for teaching roles if a Catholic cannot be found. This could be for maths teachers, PE teachers, science teachers or any other role.

(Incidentally, ‘faith’ schools’ broad ability to discriminate in this way is possibly a breach of the European Employment Directive, which limits the extent to which schools can discriminate to where it can be said that there is a genuine occupational requirement (GOR). An example of a GOR is requiring a priest to share the faith of his or her church. There cannot possibly be said to be a GOR on every teacher at a school. For this reason, in 2010 we complained to the European Commission and said that UK law is in breach of European law in allowing such widespread discrimination. In 2012 the Commission took this up as a formal investigation.)

10. Until recently, if a science exam question conflicted with a religious belief, the question could be removed

Last year a state-funded and one independent Charedi Jewish school were found to have been blacking out exam questions on evolution in its GCSE science exams. The state school claimed that the practice of censoring questions had ‘successfully been in place within the Charedi schools throughout England for many years’. Most worryingly, when this came to light, Ofqual and the exam boards initially decided to support the practice.

However, after public pressure, Ofqual and the exam boards thankfully decided to reverse their previous decision and the practice is now banned.

More generally we do occasionally see concerns about the teaching of evolution or creationism in state schools – and the problem is widespread in private schools, many of which are getting state funding through their nurseries.

How are the schools funded?

Voluntary Aided schools have 100% of their running costs and 90% of their building costs met by the state, with the remaining 10% building costs being paid for by the religious organisation. But this comes to about 1-2% of the schools’ total budget and so is typically fundraised off the parents in much the same way that all schools fundraise. Furthermore it is waived for big building projects (through both the Building Schools for the Future and Priority School Building Programme schemes). And other types of ‘faith’ school do not have to pay a penny – including Academies which have converted from being Voluntary Aided.

Conclusion

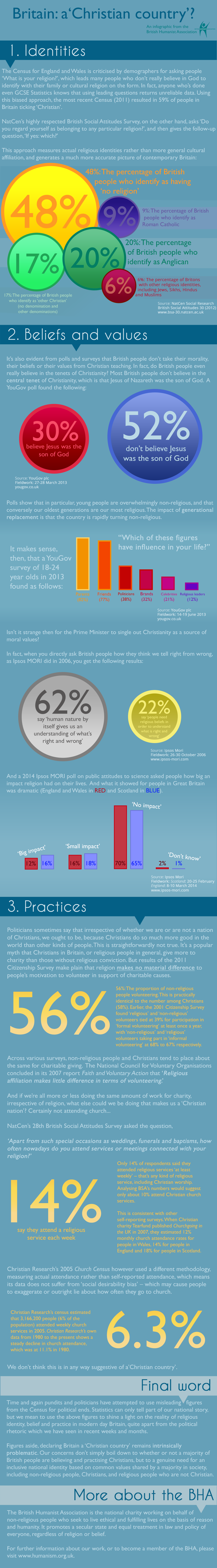

In sum, these religious schools are virtually 100% funded by taxpayers, even though 58% think they should not be and 70% think we shouldn’t be funding the promotion of religion in schools at all.

Not all religious schools discriminate in all of the ways we have set out. But the fact that some of them do so must surely be of grave concern. We think it’s wrong that schools segregate children on the basis of their parents’ religion, can similarly discriminate against teachers and can also teach a curriculum that comes from a perspective that is narrow and unshared by those of other faiths or those of none.

Instead we would like all state schools to be equally inclusive of those of all religious and non-religious beliefs. It is only if this is the case that we can pass on to future generations a tolerant, harmonious and cohesive society in which everyone is treated fairly and equally.