It’s as though a door opened and someone beckoned; I didn’t respond, and the door was closed for always. I was still a non-believer, but not so militant now – perhaps because of that little Madonna, or because of my friend Maria who trusted in that God of hers in spite of everything.

These are the words of my narrator Jane Lambert. She has had one of those uplifting subjective experiences – the kind we call ‘transcendental’ – in front of an exquisite painting of the Madonna and Child, in the company of her Catholic friend, Maria.

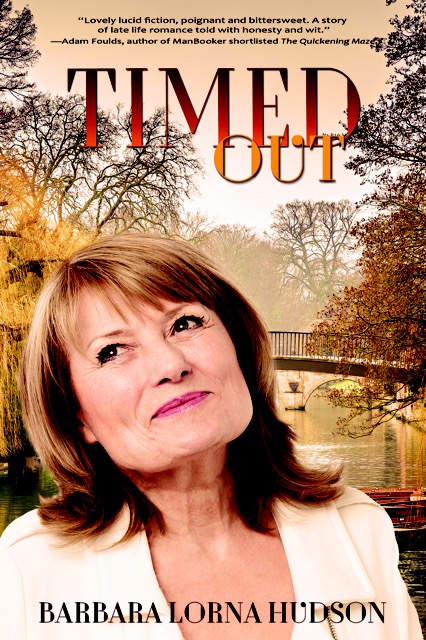

My novel Timed Out is about ageing, Internet dating and also about Humanism. Perhaps not an obvious combination.

This is how the story took shape. The germ of the idea came when I myself retired and found myself asking what is the point of me? I think a lot of us, especially if we are without close family and have been totally absorbed in a career, do wonder that, and cast around for ways to find fulfilment and a meaning for our retirement years.

My protagonist Jane embarks on a search for a partner via Internet dating, and her longing to love and be loved is the dominant storyline. And as she embarks on her new life, she continues to wrestle with the big unanswered questions. She has her ‘religious moments’ – but do they signify anything supernatural?

‘As you age, you see death approaching and you take stock. You wonder about the future and what it’s all for, and you still have those moments when you get a sort of inkling that there might be more …’ A Catholic funeral, a visit to Auschwitz, and memories of growing up in a village full of bigoted Chapel people, all help Jane to clarify her ideas.

The main challenge of this novel was to weave these strands together – Jane’s relationships (it would have been so much easier to focus solely on her quest for love) and the Big Questions. For example, the funeral episode involves the beauty of religious ritual, the nonsense of religious dogma, Jane’s sense of loss and loneliness, and her relationship with her atheist friends. A visit to Auschwitz leads naturally to questioning of the existence of God and also sets the scene for a growing closeness between Jane and the man she is with.

Despite my USP of an older woman and Internet dating, Timed Out was judged to be ‘not commercial’ by several agents. A report by a senior figure in one of the major publishing houses stated unequivocally that the reading public do not want to read about religion – whether for or against. Novels have always been explorations of the human condition. How can we interest readers in stories that do this from a humanist perspective? I think an absorbing story and non-believer characters they can identify with should help. It’s not easy, though. I wish more humanist novelists would take up the challenge.

Barbara Lorna Hudson is a novelist, as well as a former psychiatric social worker, marital therapist, and an Oxford don. Her novel Timed Out is available to buy on Amazon.