Heroes are not the stuff of myth: they keep us safe each and every day

It’s normal when confronted by horrific events someplace in the world to feel a mixture of emotions. Grief, for the victims whose stories you have read about in the papers. Anger, for the fact that such a tragedy could be allowed to happen. Despair, that the world is in such a rotten state that such horrors can occur. Relief: that it didn’t happen to someone you love. Guilt, for thinking that.

Last week’s terror attack came closer to home, and for many these feelings were heightened. Among those, something else: fear. When the unthinkable happens, what do we do? In moments like these, it’s natural to feel hyper-aware of one’s own mortality and to think of all the people we cherish. We become aware of life’s fragility. We reflect on how important it is to tell the people we love that we love them.

This fragile, precious life is the only life we’ll ever have. It makes sense to make it count, and most of us will try our bests to lead positive, happy existences that do not cause harm to others. It is a sad fact of existence, however, that some people mean to cause harm. When they do, and when tragedy strikes, it is profoundly traumatic. It shakes us. And it brings home just how much we owe to those extraordinary people who put themselves in harm’s way to keep us safe, to keep us healthy, to keep us alive.

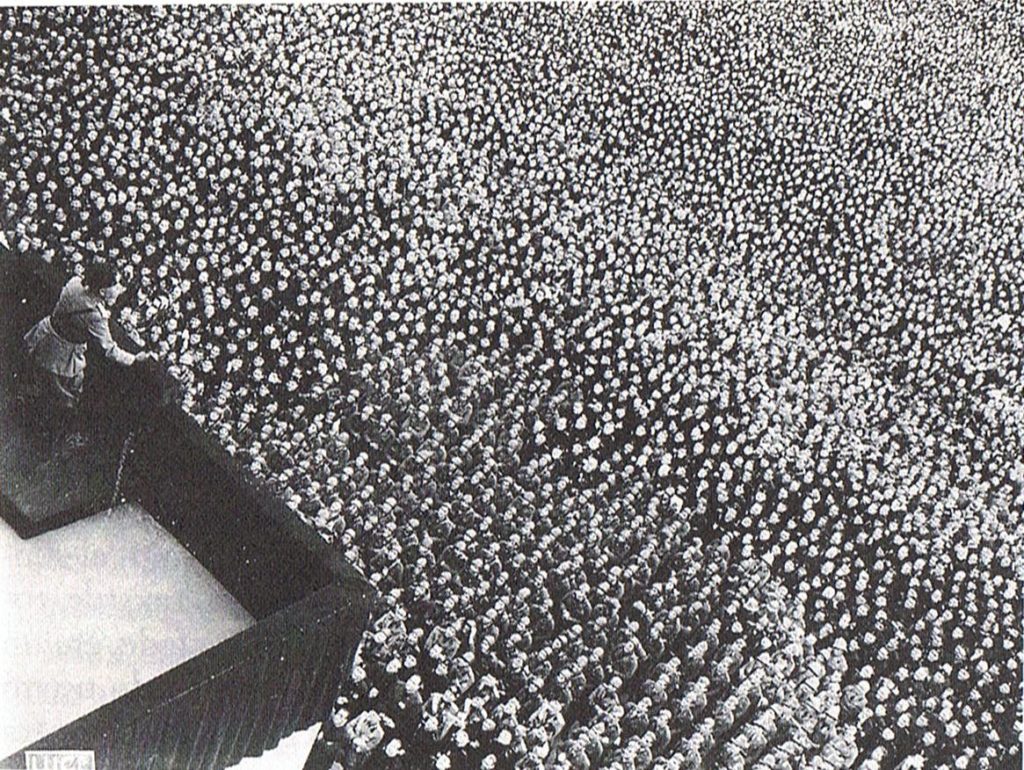

When the gunshots rang out at the Palace of Westminster last week, many people fled. But while police rushed passersby away from the scene, their colleagues ran towards the fray. Nearby hospital workers leapt from their posts… and ran towards the chaos. PC Keith Palmer, in the course of protecting civilians, was mercilessly stabbed to death by a fanatical Islamist and terrorist who had already murdered several others with his car that afternoon. We are moved by the heroism of Keith Palmer and all the emergency services workers, and by the incredible job they did that day, and do every day, to keep all of us safe. It is to their credit that the casualties of this terrible incident, though severe, were not so much greater.

Life is fragile. Life is short. Life can be lonely. It can be sad. And grief can seem too much to bear. But it is thanks to the everyday heroism of individuals like Keith Palmer that we are able to make so much of such short lives as we have. They afford us space to experience the very best of the human condition: things like love, happiness, fulfilment, the comforts of family. We all must realise that as human beings, our lives are inextricably linked. All of us must cherish those bonds, for they make us who we are and give us license to live our lives in the ways we choose. And this is just as true: we must remember, and pay tribute, to the brave individuals who make the good possible. Thank you.