This blog is part of a series of perspectives on the EU referendum from prominent humanists on either side of the debate. Each puts forward a humanist case for the United Kingdom either remaining a member of, or leaving, the European Union. All six perspectives are linked in the image below.

David Pollock: The EU is an invaluable venture in pooling sovereignty in a shrinking world

The referendum campaign is immensely depressing for many reasons. For one, the two sides are merely shouting at each other, not engaging. For another, when all the best qualified institutions and experts agree that leaving the EU would be economically damaging, the Brexiteers respond only by invoking a corrosive and irrational distrust of experts, emulating the worst ways of conspiracy theorists. Moreover, their ramshackle coalition of rackety discontents from across the political spectrum cannot agree on any alternative economic policy, flinging out as many unformulated ideas as they have ways of spending the cash putatively saved by quitting. On the other side the Remain campaign has so far failed to respond to people’s worries about immigration: indeed, they are now reaping the whirlwind many of them had previously sown in their distorted and one-sided presentation of immigrants as scroungers and health tourists.

Sadly the EU has for decades been subject to a campaign of systematic distortion and lies in the proprietor-owned press. Even the BBC, in the interest of balance, is now presenting a distorted picture, reporting equally the lies of the Brexiteers (‘£350 million a week for the NHS’) and the sober warnings of the Institute of Fiscal Studies.

The issues are far too important to be so demeaned. The EU is an invaluable venture in pooling sovereignty in a shrinking world. So far from representing a surrender, it offers Britain, with its mature democracy and pragmatic politics, a platform for wider international influence. It is undoubtedly imperfect (as in our own sphere the history of the European Humanist Federation’s engagement under Article 17 of the Lisbon Treaty shows) but in its espoused principles and standards (and devices such as its Ombudsman who in that case found for the EHF over the Commission) it contains the mechanisms for self-correction.

Indeed, the EU offers great promise for the future: it deserves commitment, not sabotage. The hated Brussels bureaucrats are the servants of the Council of Ministers, doing the will of governments and subject to their control. Just as our own Parliament had to fight over centuries for its powers, so the European Parliament is demanding – and gaining – more influence and powers. Already EU regulations – collaboratively adopted by all EU members – are improving our own standards in (for example) workers’ rights and environmental protection, providing a collaborative bulwark against big business’s devotion to short-term profit that individual nations are increasingly powerless to resist. It is the EU that is standing up to US-based multinationals over taxation, privacy and monopoly power. The EU’s Charter of Fundamental Rights and the associated agency are valuable backing for the Council of Europe’s Convention on Human Rights. Its freedom of movement may bring low-paid eastern European migrants here – largely to do jobs that no-one else will take – but it is a huge benefit for those who remember queues and delays at endless national frontiers and a necessary corollary of the freedom of trade that boosts business efficiency and the prosperity of us all.

The EU was a great promoter of human rights and rule of law in eastern Europe, setting standards that candidate member states had to meet and maintain. The narrow nationalism of the Brexiteers, however, lends comfort to their confrères in unsavoury populist parties such as are now in power in Poland and Hungary and their even more dubious allies in neo-fascist and similar parties in France, Austria, Germany and elsewhere. These also play on anti-EU nationalism and atavistic appeals to past greatness. The way to resist such dangerous trends – and they are genuinely dangerous – is not to pander to them by walking away and so weakening the democratic forces in the EU: it is to stand up to them and engage in the argument, advancing cooperative internationalism rather than putting up the shutters and ushering in another age of unconstrained nationalistic rivalries. As so often, it is hard work, not extravagant gestures, that are needed.

No human institution is without fault, and the EU is obviously no exception, but it is a strong force for good and well worth defending in this referendum campaign and then reforming from the inside rather than petulantly quitting and pouring scorn on it powerlessly from afar.

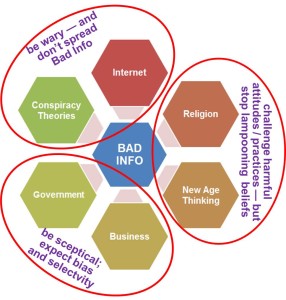

Be vigilant – make sure that ‘a little red light’ comes on in our head whenever you get near to an ‘intellectual black hole’ so that you don’t get sucked in / fall victim.

Be vigilant – make sure that ‘a little red light’ comes on in our head whenever you get near to an ‘intellectual black hole’ so that you don’t get sucked in / fall victim.