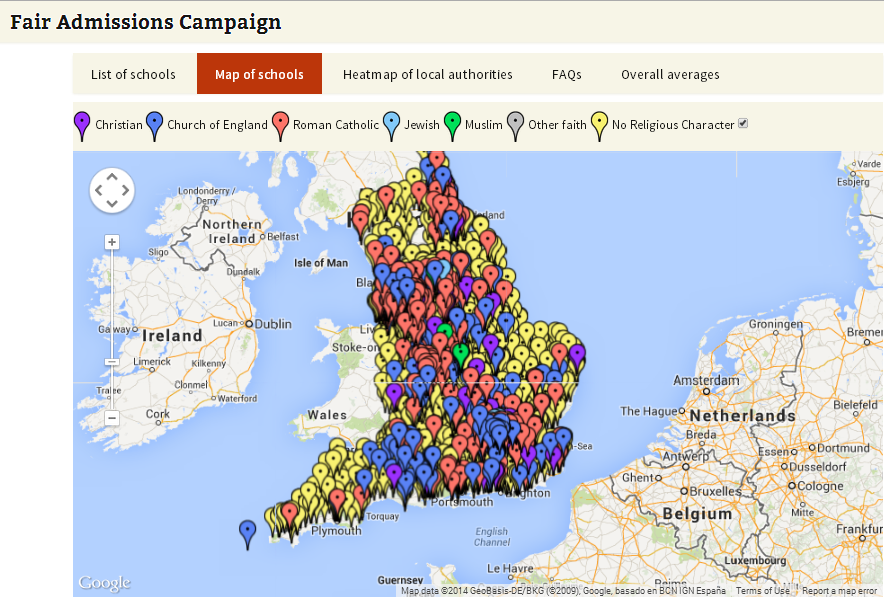

Children are naturally curious. But they’re also susceptible and impressionable. Emma C Williams shares her experience of education in a ‘faith’ school – but does it match up to yours?

My school was proudly old-fashioned. Questions were viewed with suspicion and contempt, especially in the context of religion. We were not allowed to study RE as a subject, since exposure to a variety of religious views would have ‘confused’ us. Instead, we had Divinity with the School Chaplain: we read passages from the Bible and he explained them.

My parents were deliberately neutral in their stance, and so I came to my religious schooling with a completely open mind – in many ways, an easy convert. I was profoundly respectful of what I assumed were the sincerely-held beliefs of those around me and I would bow my head during prayers. I was utterly fascinated by the ritual of Chapel, and knew all the traditional hymns; I can still sing most of them all the way through, much to my husband’s consternation, and can recite the Creed, some of the Psalms, the Lord’s Prayer and several others.

While I would listen with interest during the Sermon, it took me a long time to realise that I was pretty much the only one doing so. On an increasing number of occasions I would find myself enraged by the message that we had been given in Chapel, or puzzled by the hypocrisy of our situation. If Jesus said to ‘sell all thou hast and give to the poor,’ what were we doing in an expensive boarding school? Did God honestly care how I performed in my exams – didn’t He have something more important to worry about? And why on earth did I have to pray for the Queen? Ignored by the staff and ridiculed by my peers, it became clear to me that most people neither listened to nor cared about the lessons that we were taught by the Reverend. Even he didn’t seem to care that much. Yet when I questioned the charade, I was bullied for it – by students and some of the staff.

Atheists are often accused of being ‘angry’ and I guess it’s hard for believers to comprehend the unpleasant mix of condescension, prejudice and paranoia that some of us have faced, growing up in a society that tends to equate faith with morality. Soon after I started attending school, I went to a meeting that was announced for ‘all students who are not Christians.’ In my innocence, I failed to realize that this was a euphemistic way of gathering our tiny handful of Muslim students so that their non-attendance at Chapel could be agreed. The Housemistress nearly fainted when I showed up, the only girl in the room without a headscarf. She asked me what on earth I was doing there, so I explained that I didn’t believe in God and was therefore not a Christian. She told me not to be so ridiculous, said that my views ‘didn’t count’ and sent me away. That was probably the first time that I felt really angry.

Despite the pressure (or perhaps because of it – I was a rebellious child at heart), I became more and more convinced during my childhood that an unswerving acceptance of a bundle of ancient writings made very little sense. In addition, a school rife with bullying was a fine place to observe that religious beliefs have no effect on a person’s humanity. Over the years I watched some of the worst bullies in the school pass through their Confirmation ceremony, in which they agreed to ‘turn away from everything which was evil or sinful.’ Some of them became servers in Chapel. My distaste for the whole sham increased, and by the time I reached University I was thoroughly relieved to be away from it.

Yet given that we’re all a product of our experiences, I sometimes wonder what kind of person I would be had I not attended such an old-fashioned ‘faith’ school. I fully support the BHA’s campaign against them, as in principle I believe that every child should have an education that is free in every sense – not least free from indoctrination and prejudice. Yet for me, my experiences shaped my convictions – and not in the way that the school had intended. Maybe I’m unusual, but if my story is anything to go by and you want to nurture an atheist, then I guess you proceed as follows: send them to a ‘faith’ school, ladle on plenty of hypocrisy and tell them not to ask questions. The result may surprise you.