Jeremy Rodell discusses the meaning of ‘secularism,’ among other things. Note: this article first appeared on Sarah Ager’s Interfaith Ramadan blog.

What is Secularism?

Let’s start with what secularism means to secularists.

The British Humanist Association (BHA) defines secularism as ‘the principle that, in a plural, open society where people follow many different religious and non-religious ways of life, the communal institutions that we share (and together pay for) should provide a neutral public space where we can all meet on equal terms. State Secularism, where… the state is neutral on matters of religion or belief, guarantees the maximum freedom for all, including religious believers.’

The UK’s National Secular Society (NSS) adds that it’s ‘not about curtailing religious freedoms; it is about ensuring that the freedoms of thought and conscience apply equally to all believers and non-believers alike.’

So a secular state does not mean denying the role of Christianity and other religions – for both good and ill – in history and culture. It does not mean that religious people must forego their principles if they enter public life. Perhaps most important of all, it does not mean a society lacking in values. There’s a fairly clear set of liberal, human values shared by the majority in the UK and most other western countries, including freedom of speech, thought and belief; respect for democracy and the rule of law; equality of gender, age and sexual orientation and the view that fairness and compassion are virtues. Many of these values are enshrined in law.

The BHA and the NSS really ought to know what they’re talking about here. Unfortunately, many people, usually people who are not themselves secularists, use ‘secularism’ interchangeably with ‘atheism’ or ‘Humanism’. The previous Pope even talked of “militant Secularism”, meaning “militant Atheism” (despite the fact that the weapons used by ‘militants’ like Richard Dawkins are writing books and giving lectures, not planting bombs). But you can be religious and secularist. In fact the unequivocally Muslim, anti-Islamist campaigner, Maajid Nawaz, has just become an Honorary Associate of the NSS.

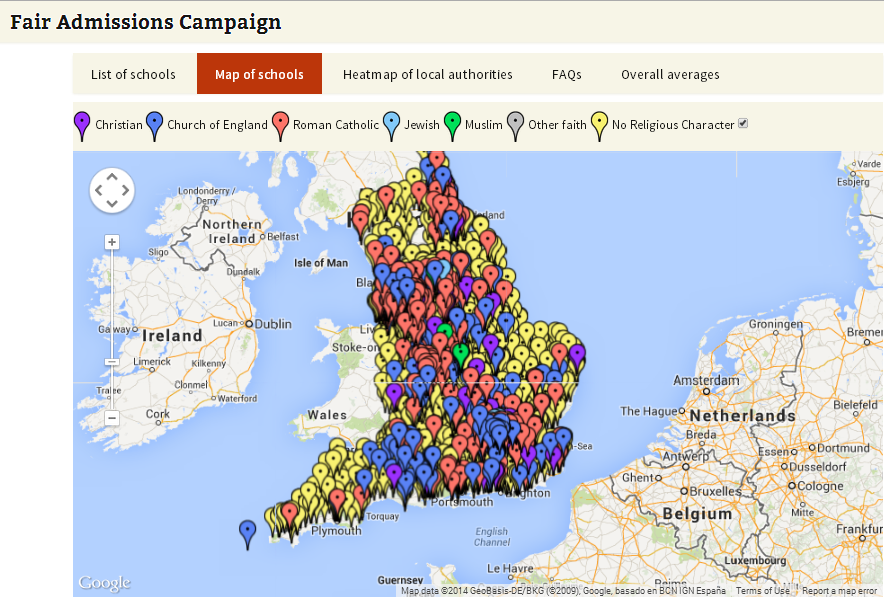

The reason for this confusion is that western countries have only become secular – to varying degrees – after many centuries in which the Church was a major power in society and there were constraints on freedom of thought and expression. Much of that power has been eroded since the Enlightenment, but battles are still going on. For example, 26 unelected bishops remain sitting as of right in the British Parliament, and many state-funded schools can discriminate in their admissions simply on the basis of parental belief. It’s no surprise that the protagonists in these battles are usually churches on one side, and humanists and other atheists on the other. If you’re on the side of the churches, it probably feels that secularism and atheism are the same thing – The Enemy.

That’s a mistake. Not only does it ignore the common ground between Christians and humanists, but it focusses on loss of religious privilege and influence, ignoring the fact that Secularism also guarantees freedom of religion and belief, and the freedom of thought and expression that goes with it. That’s important, given the realities of faith and belief in much of the modern world.

Growth of pluralism

According to the 2013 British Social Attitudes Survey, 51% of the British population are now “Nones” – people who do not consider themselves as belonging to any religion. It was 31% in 1983. Only 16% are now Anglicans, the Established Church (40% in 1983), 12% non-denominational Christians, such as African Pentecostal (3% in 1983), 9% Catholics (10% in 1983) and 5% Muslims (0.6% in 1983), with Hindus, Sikhs, Jews, Buddhists and other types of Christians making up most of the balance (all under 2%). Within each of these groups there is a lot of diversity: at least 10 different sects comprise the 5% Muslims, and the 0.5% British Jews range from ultra-Orthodox to Liberal. So we’re seeing both a big decline in religiosity and an increase in pluralism. It’s hard to imagine a more plural global city than London.

In many non-western countries, the inter-connectedness of the modern world, and wider awareness of differing beliefs – including Atheism – is also tending to increase pluralism, or at least the desire for pluralism. At the same time, it is increasingly under threat, often because of war and the active spread of an intolerant Wahhabi strain of Islam.

Secularism versus oppression

Secularism is as necessary to protect believers from other believers as it is to protect atheists.

You can currently be put to death simply for the ‘crime’ of atheism in 13 countries, according to the International Humanist andEthical Union’s 2013 Freedom of Thought Report. Saudi Arabia has now passed a law declaring atheists to be terrorists. In Mosul, in northern Iraq, there has been a Christian community for around 1600 years. In 2003 there were 70,000 Christians living there. Now ISIS have taken over and they have all fled. In Burma the government seems to be doing little or nothing to stop extremist nationalist Buddhist groups from massacring Rohinga Muslims. In Pakistan there’s growing evidence of ethnic cleansing of Shia Muslims by Sunni terrorist groups – the word ‘genocide’ is appearing – and it is illegal for Ahmadiyya Muslims to claim to be Muslim. Often they are simply killed. In Malaysia, Christians have been legally forbidden to use the word “Allah” to refer to God, even though they have been doing so for hundreds of years. In Iran there is institutionalised persecution of Baha’is .

Sadly, there are many other examples where the response to pluralism is oppression. Often it’s entwined with political power, driven by fear of losing power – or simply of change – and lack of confidence that the favoured belief will succeed in a plural environment.

Secularism is the alternative response to pluralism. Ideally it’s complemented by the type of mature democracy that avoids “winner takes all” outcomes such as we saw in Egypt under President Morsi.

The faithful need secularism because it guarantees their freedom, and in some cases their survival. It is the only alternative to oppression in a fast-changing, inter-connected plural world.

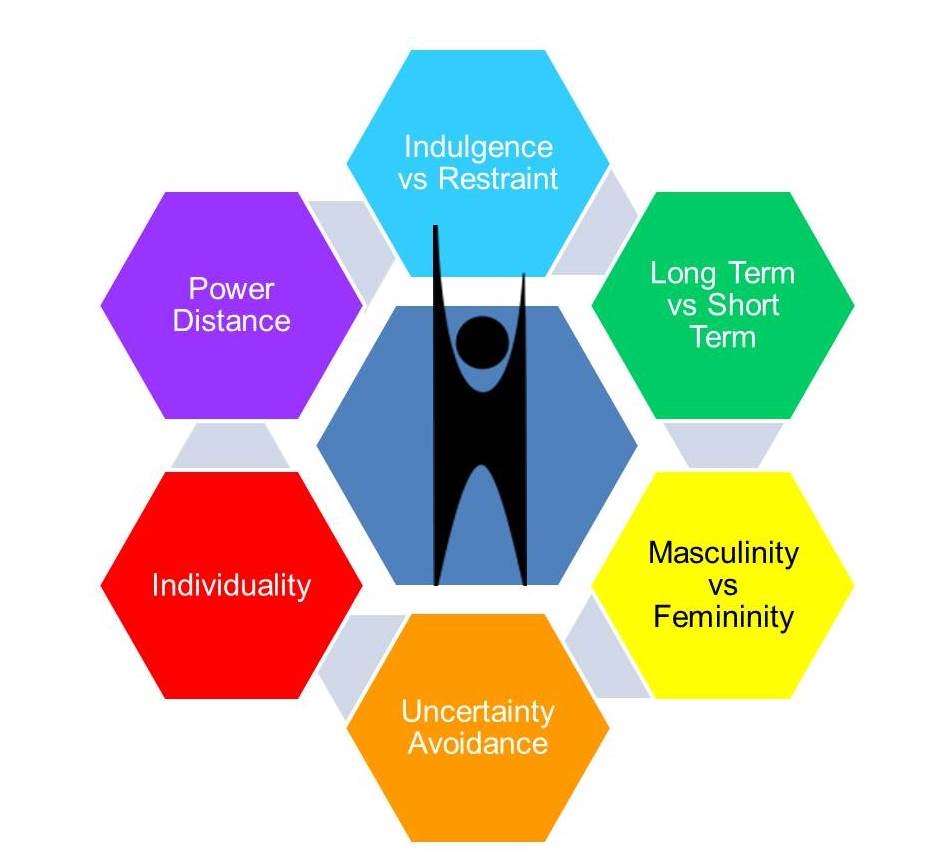

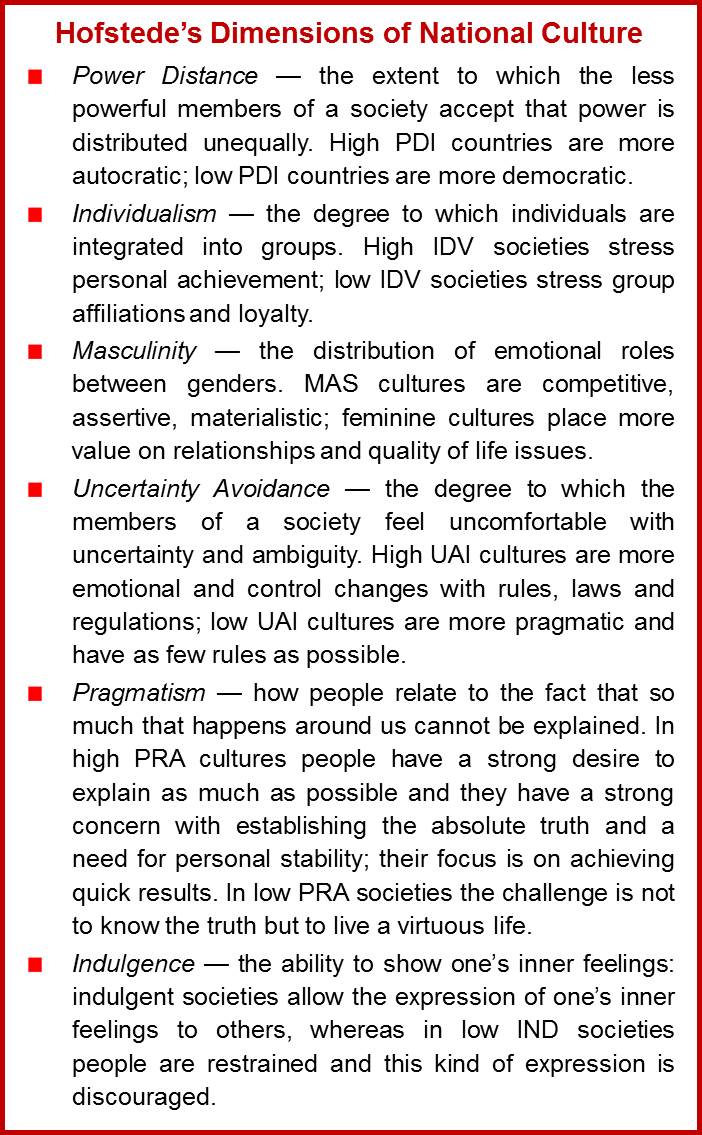

In May, Milton Keynes Humanists held a meeting on ‘Cultural Diversity,’ at which we explored various ways in which social scientists had attempted to describe and classify different cultures. We were particularly interested in the work of Geert Hofstede, and we thought it would be fun to see how our group scored on the different dimensions of culture that he has identified. For a small fee (

In May, Milton Keynes Humanists held a meeting on ‘Cultural Diversity,’ at which we explored various ways in which social scientists had attempted to describe and classify different cultures. We were particularly interested in the work of Geert Hofstede, and we thought it would be fun to see how our group scored on the different dimensions of culture that he has identified. For a small fee ( Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture

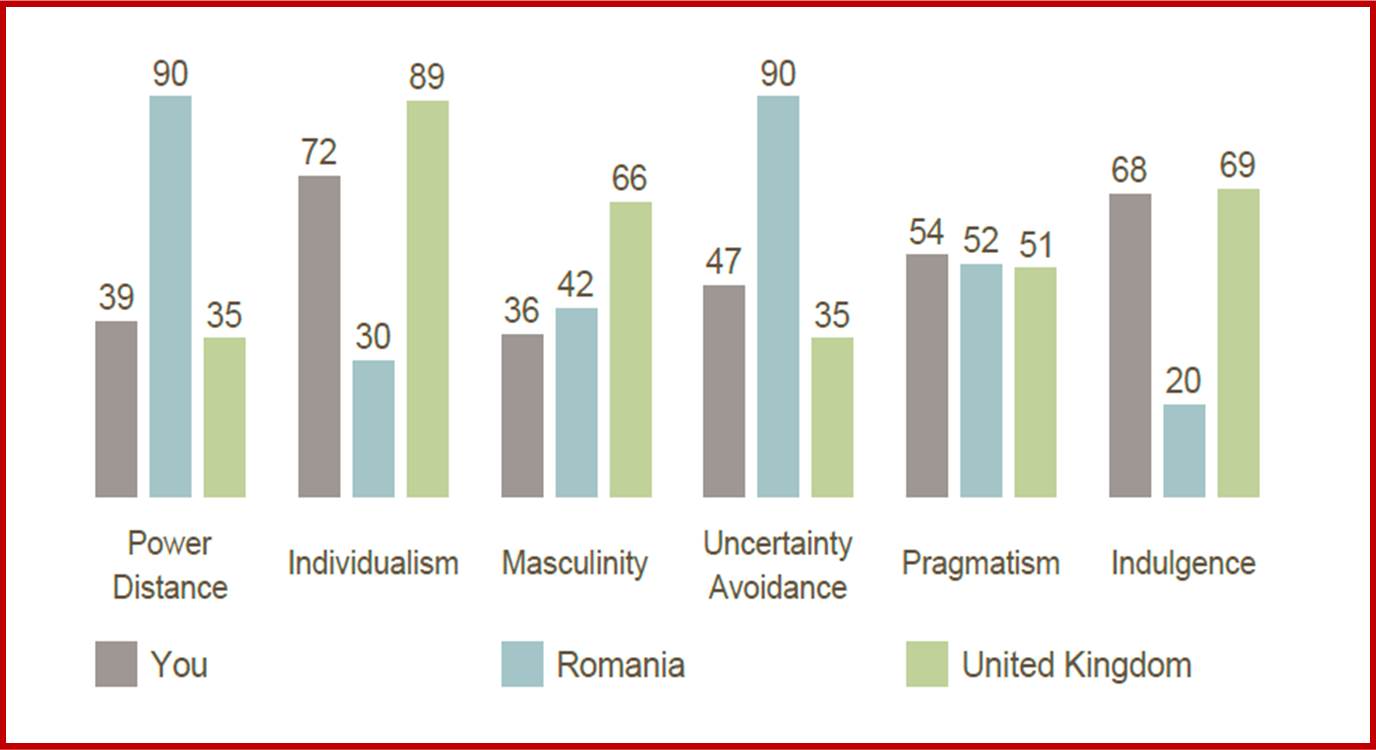

Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture If you look at British culture through the lens of the Hofstede 6-D Model you find that we have high scores on INV, MAS and IND — indeed, at 89 the UK is amongst the highest of the individualistic scores. The figure for Masculinity (66) is lower, but Britain is still ‘highly success oriented and driven’; and the figure for INV (69) suggests that we ‘exhibit a willingness to realise our impulses and desires with regard to enjoying life and having fun.’

If you look at British culture through the lens of the Hofstede 6-D Model you find that we have high scores on INV, MAS and IND — indeed, at 89 the UK is amongst the highest of the individualistic scores. The figure for Masculinity (66) is lower, but Britain is still ‘highly success oriented and driven’; and the figure for INV (69) suggests that we ‘exhibit a willingness to realise our impulses and desires with regard to enjoying life and having fun.’ To prepare our group’s profile we averaged the scores and chose the closest integers; and where the average was X.4, X.5 or X.6 we made an assessment based on the score chosen by the majority. We are not making any great claims for this exercise, only that our results are interesting and deeply thought-provoking. For example, it turns out that our members are close to the UK norm in three of the Hofstede dimensions (PDI, PRA & IND) but 45% lower in Masculinity, 19% lower in Individualism, and 34% higher in Uncertainty Avoidance. Whether the gender make-up of our small sample (60% men; 40% women) significantly influenced the results is not clear. And we should also repeat the Centre’s caveat that one’s scores are ‘only an approximation on Hofstede’s dimensions and not scientifically valid, because culture does not exist at an individual level’.

To prepare our group’s profile we averaged the scores and chose the closest integers; and where the average was X.4, X.5 or X.6 we made an assessment based on the score chosen by the majority. We are not making any great claims for this exercise, only that our results are interesting and deeply thought-provoking. For example, it turns out that our members are close to the UK norm in three of the Hofstede dimensions (PDI, PRA & IND) but 45% lower in Masculinity, 19% lower in Individualism, and 34% higher in Uncertainty Avoidance. Whether the gender make-up of our small sample (60% men; 40% women) significantly influenced the results is not clear. And we should also repeat the Centre’s caveat that one’s scores are ‘only an approximation on Hofstede’s dimensions and not scientifically valid, because culture does not exist at an individual level’. Anyone carrying out a more rigorous analysis of the factors that make for strong humanist cultures might want to take a closer look at countries with the least institutionalised religious privilege, greatest religious tolerance, liberal legislature, etc. And in this respect we can recommend the International Humanist & Ethical Union’s recent

Anyone carrying out a more rigorous analysis of the factors that make for strong humanist cultures might want to take a closer look at countries with the least institutionalised religious privilege, greatest religious tolerance, liberal legislature, etc. And in this respect we can recommend the International Humanist & Ethical Union’s recent