As a charity that operates within the field of religion and belief, the BHA’s work on education issues tends to be associated most with its campaigning on ‘faith’ schools and against the various freedoms to discriminate along religious lines that they enjoy. What we are less well-known for, perhaps, is our decades of campaigning around the importance of personal, social, health, and economic education (PSHE) and relationships and education (RSE), and on the many benefits that making the subject compulsory in all schools would bring. For us, this is an issue no less important, and on which we have been no less active.

For the past few years, for instance, we have sat on the advisory group of the Sex Education Forum (SEF), helping to guide the wider movement that provides and campaigns for comprehensive, high-quality RSE. We are an active member of the Children’s Rights Alliance of England, and sat on the working group that drafted the education section of the Civil Society report to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, again recommending statutory RSE in all types of school. And in recent months we have submitted evidence on the need for high-quality PSHE and RSE in schools to every official consultation on children’s rights and wellbeing, including to all five of the parliamentary committees whose subsequent recommendations to Government proved so pivotal in finally provoking action.

This is not to mention, of course, the landmark report we published earlier this year, Healthy, happy, safe? An investigation into how PSHE and SRE are inspected in English schools, which revealed that Ofsted has been ‘almost totally neglecting’ RSE and PSHE in school inspections. The report was vital in undermining the Government’s claim that statutory PSHE and RSE was unnecessary given that Ofsted is effectively guaranteeing that the subject is taught through its inspections – one less excuse for the Government to turn to in trying to quiet the increasingly noisy consensus.

Our attention in recent weeks, however, has been focused on Parliament, and specifically on seizing the opportunity to secure compulsory PSHE and RSE through an amendment to the Children and Social Work Bill. This is a move the Government itself has now made, of course, but if it seemed as though it did so with minimum fuss, that is because the headlines tend only to reflect what happens on stage, rather than what goes on behind the scenes.

There were no reports, for instance, of our appeal encouraging members of the public to write to their MPs in support of statutory RSE, nor of the hundreds of MPs who subsequently received emails from thousands of their constituents at the prompting of the BHA, the Sex Education Forum, the Terence Higgins Trust, and a host of others. There were no reports of our meetings with the Department for Education and with the opposition front bench the week before the Government finally published its proposals, nor of the meetings held with the MPs who ‘showed the way’ to Government in tabling their own amendments and securing support for them.

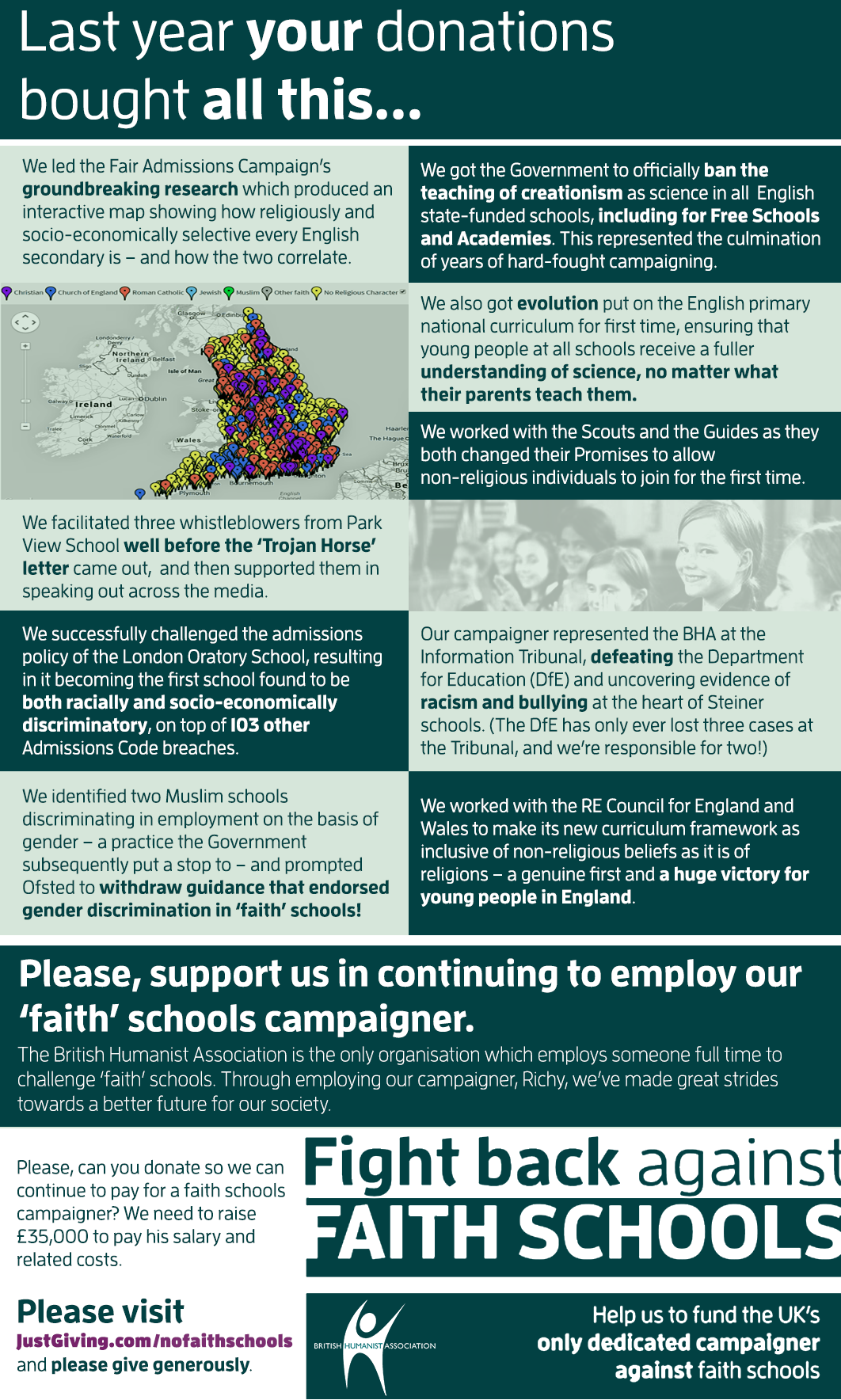

There also were no reports (unsurprisingly) of a website we set up with SEF to ‘track’ the views and voting intention of MPs should it come to a vote – a website that frustratingly never had the chance to launch in the midst of all the toing and froing between Parliament and Government. The website compiled the views of every MP on the subject of statutory status and presented all their public positions, showing in each case whether they were known to be supportive, hostile, or neither, and how close we were to reaching the tipping point of majority support. Unfortunately, the complex way in which Labour and Conservative backbench amendments evolved, prior to the Government finally coming on board, meant that the time never proved right to actually launch the website. But the threat of the site and the tracking exercise it entailed – systematically identifying dozens of Conservative MPs in particular who were speaking out in support – was hugely beneficial in applying private pressure on the Government to get things over the line.

From the ‘MP tracker’ website, showing which MPs support statutory SRE, didn’t support it, or whose views were unknown.

Last, but by no means least, there were no reports of the collaboration and coordination within the charity sector, which saw the BHA, Sex Education Forum, the PSHE Association, the Terrence Higgins Trust, the National Children’s Bureau, Barnardo’s, NSPCC, Stonewall, Girlguiding, End Violence Against Women, Plan UK, and others all working together. Without the joint work of this coalition, Whitehall’s dithering and prevarication on making RSE statutory would doubtless have continued.

This is not to say that the campaign is over, however. The Government is still to draw up the regulations and guidance that will dictate the nature of the RSE that schools must provide. The devil will be in the detail, and we have already voiced concerns about the Government’s promise that ‘faith schools will continue to be able to teach in accordance with the tenets of their faith’. If you’re wondering what this might mean in practice, you need only look to our previous work.

In 2013 we identified 46 schools which, in their RSE policies, either replicated section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 (which forbade local authorities from promoting homosexuality in schools), or stated that the law (which was repealed in 2003) was still in force. Similarly, just last year, through our blogging and whistleblowing website Faith Schoolers Anonymous, we revealed that the RSE policy of a Catholic secondary school in England stated that it ‘cannot approve of homosexual genital acts’, asserting that ‘a homosexual partnership and a heterosexual marriage can never be equated. And our same website has recently highlighted the many lies of the religious sex education movement, ranging from claims that the cervical cancer jab ‘gives young people another green light to be promiscuous’, to the assertion that children’s reproductive-health rights are ‘a euphemism for the “right” of children to engage in unlawful sexual intercourse, with confidential access to contraception and abortion.’

As ever, then, our campaigning must continue. And we’ll keep plugging away, both publicly and in private, to try to effect change in all schools, including those of a religious character.