Aniela Bylinski discusses her journey to Humanism.

A parent’s work is never done, the saying goes. Photo: Marina del Castell.

As a new parent in 2009 my world opened up to a new way of life. I had a baby which was reliant on me for food and shelter, care and affection. After a few months of getting to know my baby and getting into a new routine which worked for both of us, well mainly her, I started to think about what I was going to tell her, what my truth was, and what her truth might one day be.

I made conscious decisions to be her sole carer for the first 12 months at least, and to support her emotionally and physically as much as I could, without taking away her independence. I also reflected on my own childhood and made decisions about which bits were good or bad, what I might use myself or not.

People around me were having their children christened and becoming part of a church or religious community, but that is not what I wanted for my children or my family. I would have liked to have been able to find a community which was consistent with my non-belief in god but unfortunately it did not exist, or so I thought.

I was asking myself questions about morality such as; if I don’t believe in god then how will I fit in with other families, how will my children be perceived? What will I teach my children about telling tales, being good and working hard, what difference will it make if they are bad, if god didn’t exist? If I don’t have my child christened what will that mean for her and her school place?

I decided that I did not want to be peer pressured into supporting a community which I did not agree with, just because it was the only one available. I had difficulty articulating my non-belief without offending people and decided to research other options which could be available to me.

I did know that I wanted my children to grow up to be open minded, critical thinkers, to question what they were told and not just accept things as a fact. I didn’t want to put any fear into them and didn’t think they had any sins which they needed to be cleansed of from birth. I knew I wanted them to be brought up to use logic and reason. But where was the community in the UK in 2009 which could provide this for me?

I looked around on the internet and found some fantastic books to read ‘Parenting Beyond Belief’ and ‘Raising Freethinkers’. These books were like a breath of fresh air, they explained how you can raise children with ethics and values confidently, without a god, they explain how you can talk to your children about death without a heaven, and they give good examples of how to tackle religious holidays. The list goes on; disciplining, sex education etc. There are loads of practical guides and exercises which you can use to teach your children how to wonder and ask questions. It also gives permission to say ‘I don’t know’ and gives you the opportunity to explore the world with your child. These books gave me the confidence to go out into the world of religion and say I’m not religious, my children may or may not be and that’s OK.

More importantly though the books lead me to Humanism and in particular the British Humanist Association. When I visited the website it reinforced what I already felt about living a life using logic and reason, to benefit the whole of humanity, I know now this was my truth.

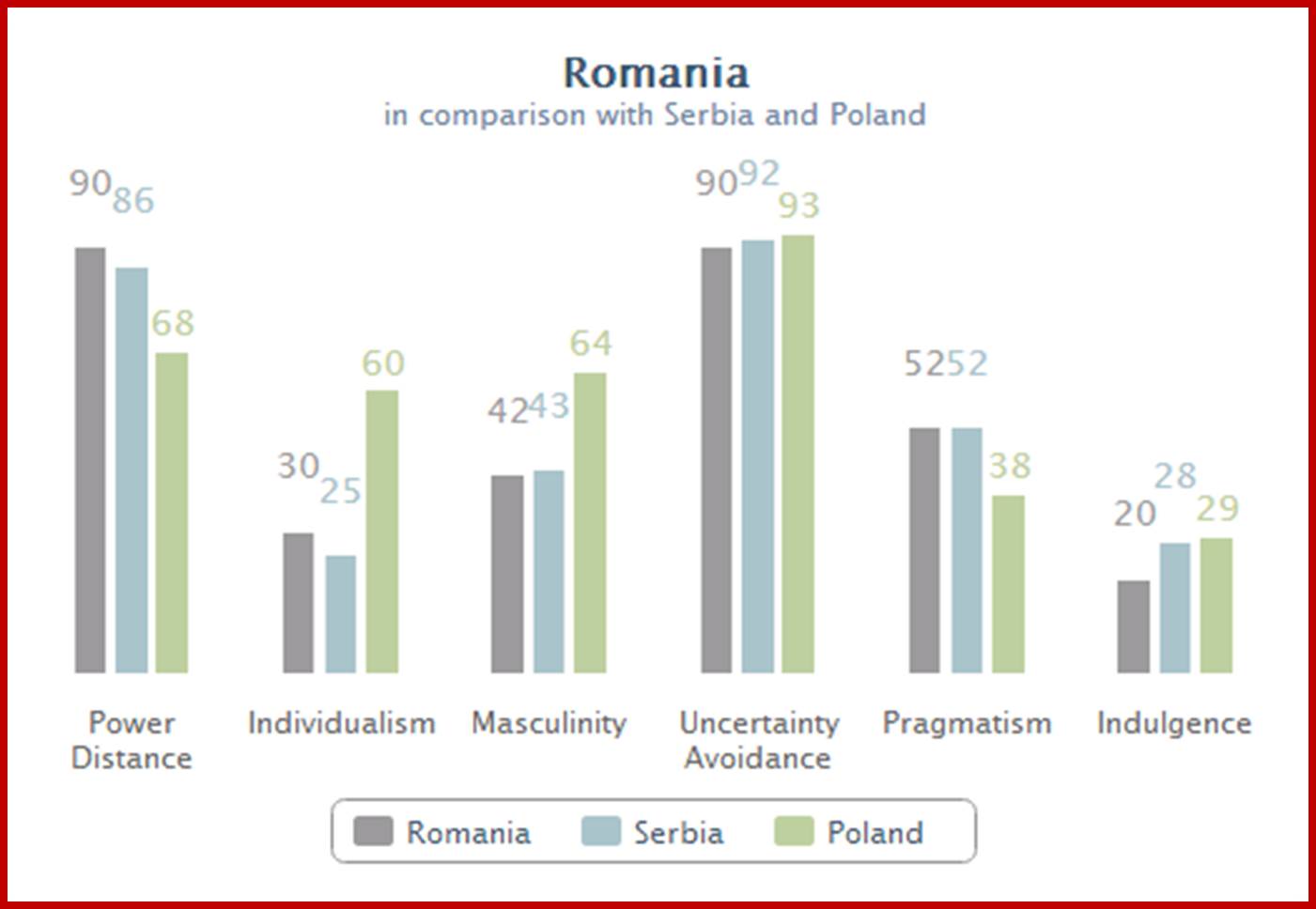

In May, Milton Keynes Humanists held a meeting on ‘Cultural Diversity,’ at which we explored various ways in which social scientists had attempted to describe and classify different cultures. We were particularly interested in the work of Geert Hofstede, and we thought it would be fun to see how our group scored on the different dimensions of culture that he has identified. For a small fee (

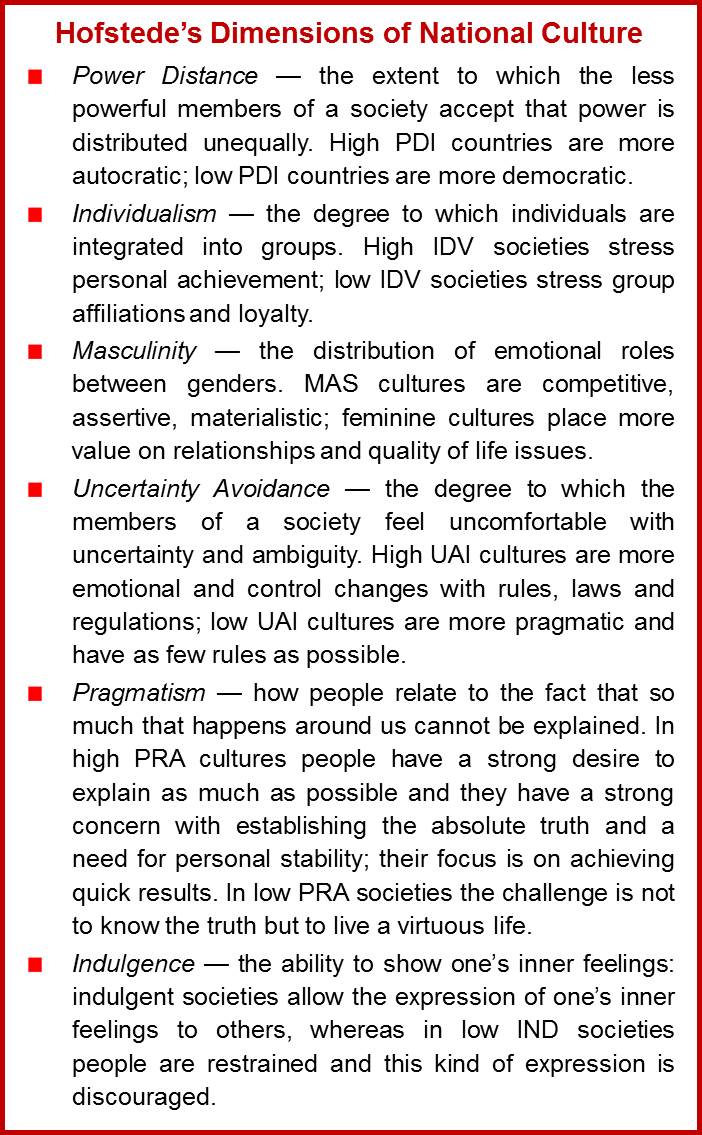

In May, Milton Keynes Humanists held a meeting on ‘Cultural Diversity,’ at which we explored various ways in which social scientists had attempted to describe and classify different cultures. We were particularly interested in the work of Geert Hofstede, and we thought it would be fun to see how our group scored on the different dimensions of culture that he has identified. For a small fee ( Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture

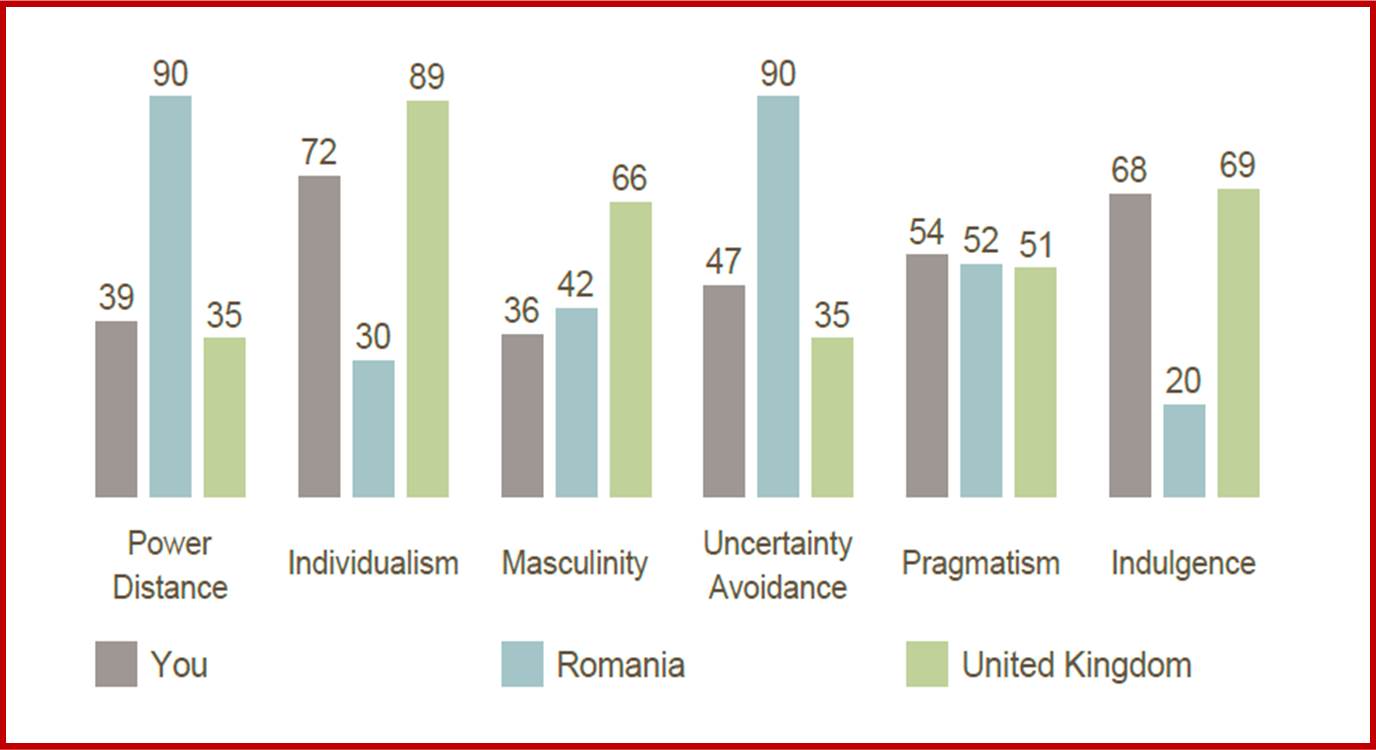

Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture If you look at British culture through the lens of the Hofstede 6-D Model you find that we have high scores on INV, MAS and IND — indeed, at 89 the UK is amongst the highest of the individualistic scores. The figure for Masculinity (66) is lower, but Britain is still ‘highly success oriented and driven’; and the figure for INV (69) suggests that we ‘exhibit a willingness to realise our impulses and desires with regard to enjoying life and having fun.’

If you look at British culture through the lens of the Hofstede 6-D Model you find that we have high scores on INV, MAS and IND — indeed, at 89 the UK is amongst the highest of the individualistic scores. The figure for Masculinity (66) is lower, but Britain is still ‘highly success oriented and driven’; and the figure for INV (69) suggests that we ‘exhibit a willingness to realise our impulses and desires with regard to enjoying life and having fun.’ To prepare our group’s profile we averaged the scores and chose the closest integers; and where the average was X.4, X.5 or X.6 we made an assessment based on the score chosen by the majority. We are not making any great claims for this exercise, only that our results are interesting and deeply thought-provoking. For example, it turns out that our members are close to the UK norm in three of the Hofstede dimensions (PDI, PRA & IND) but 45% lower in Masculinity, 19% lower in Individualism, and 34% higher in Uncertainty Avoidance. Whether the gender make-up of our small sample (60% men; 40% women) significantly influenced the results is not clear. And we should also repeat the Centre’s caveat that one’s scores are ‘only an approximation on Hofstede’s dimensions and not scientifically valid, because culture does not exist at an individual level’.

To prepare our group’s profile we averaged the scores and chose the closest integers; and where the average was X.4, X.5 or X.6 we made an assessment based on the score chosen by the majority. We are not making any great claims for this exercise, only that our results are interesting and deeply thought-provoking. For example, it turns out that our members are close to the UK norm in three of the Hofstede dimensions (PDI, PRA & IND) but 45% lower in Masculinity, 19% lower in Individualism, and 34% higher in Uncertainty Avoidance. Whether the gender make-up of our small sample (60% men; 40% women) significantly influenced the results is not clear. And we should also repeat the Centre’s caveat that one’s scores are ‘only an approximation on Hofstede’s dimensions and not scientifically valid, because culture does not exist at an individual level’. Anyone carrying out a more rigorous analysis of the factors that make for strong humanist cultures might want to take a closer look at countries with the least institutionalised religious privilege, greatest religious tolerance, liberal legislature, etc. And in this respect we can recommend the International Humanist & Ethical Union’s recent

Anyone carrying out a more rigorous analysis of the factors that make for strong humanist cultures might want to take a closer look at countries with the least institutionalised religious privilege, greatest religious tolerance, liberal legislature, etc. And in this respect we can recommend the International Humanist & Ethical Union’s recent